May 19, 2025 | 02:26 GMT +7

May 19, 2025 | 02:26 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 19, 2025 | 02:26 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

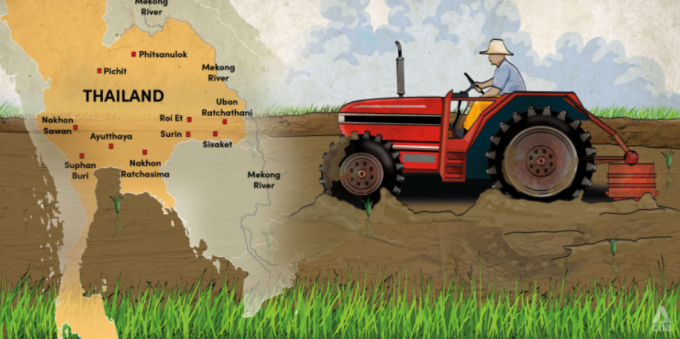

Illustration: Rafa Estrada

It has been another difficult harvest for Manas Takfaeng.

This farmer has seen plenty of seasons in his years in the fields. But now as his retirement looms closer, watching another crop suffer is hard to comprehend.

The 67-year-old is an ordinary small-hold rice grower whose family has worked the land in Ayutthaya, north of Bangkok, for generations.

The landscape has changed over the years, and now his fields flank busy roads and factories. So too has the climate.

Drought has stunted Thailand’s agricultural belt in recent years. But 2021 was meant to be different, and so it was. It was wet, but in many areas thirsty for water, the intensity and inconsistency of rain dashed hopes of a bumper harvest.

It means, yet again, the production of Thailand’s most important crop has been compromised, causing market turbulence, food security concerns and leaving millions of Thai households facing economic difficulties.

“This year, we have a lot of water. The rice doesn’t produce grains well and the yield will be less than in the years that have less water,” Manas said.

“The weather right now cannot compete with the weather in the past. Back then, rain came in its season and the weather barely changed.

“Right now, I don’t know if summer will be summer, or winter will be winter.”

Manas Takfaeng has found rice farming difficult in recent years. Photo: CNA

Further south in Prachinburi, Wichat Petchpradab watched his last harvest wallow in flood waters late last year.

Wichat, 36, rents the fields where he farms, like many who are unable to purchase their own land. With his rice submerged in waters that took an age to drain, this seasonal setback will cost him dearly.

“The fields are still flooded. The rice is rotten. I tried to harvest it but I barely got anything,” he said.

“I don’t go to the fields every day now because the more I see them, the more I want to harvest them. And the more I try, the more money I lose.”

HIGHLY VULNERABLE

Thailand accounts for about a quarter of the world’s global trade of rice. It is a critically important industry highly vulnerable to climate change, in a country ranked ninth in the world on the Global Climate Risk Index.

More frequent bouts of extreme weather - both dry and wet - can quickly cripple rice plantations. In Thailand, that has been happening with increasing regularity.

In 2019, the country experienced the lowest amount of rain for a decade, causing severe water shortages. The Mekong River fell to record low levels and rice cultivation suffered significantly.

While increased rainfall over 2021 improved overall yields, it still resulted in widespread damage in many regions.

Timing is everything in rice growing. In the past, farmers would combine weather pattern knowledge with intuition to judge exactly when to plant their seeds

Those time honoured constants of growing rice in Thailand, which many farmers still cling to, are proving futile in the face of wildly oscillating climate conditions.

Nithat Charoenthammaraksa runs a rice network, which produces and collects rice seeds for about 400 farming households. Despite providing guidance about the most suitable cultivars to plant, and supporting the growing process, he said that the past decade has been challenging.

“The situation is completely different than when I first started the network in 1997. In the present day, the problems are so severe,” he said.

“My farmers are all dedicated farmers. They pay attention to detail because we have to produce quality rice seeds. And they can’t do anything if there’s no water. Now, with regards to rain and water, it’s hard to predict. It’s such a struggle."

While Nithat’s network operates within areas that have access to a public system of irrigation from water reservoirs, others around the country that rely on rainfall are more exposed.

Across 8.1 million agricultural households in Thailand, only 26 per cent can access this irrigation system. With the majority of those farmers being ageing small operators with little education or access to technology, climate change is also expected to exacerbate inequalities.

Indeed, under different future scenarios, rice production could actually increase in irrigated areas while at the same time drastically be stunted in rainfed regions, according to research by Witsanu Attavanich, an associate professor of Economics at Kasetsart University.

Yet even under a moderate scenario, by mid-century Thailand could expect to see a more than 10 per cent decline in its overall rice yield. It would have severe flow-on effects on regional food stability.

“It's actually, very, very serious in terms of agriculture,” Witsanu said. “If we have climate change, and we have long droughts, those who stay outside the irrigated area will be gone. And that's going to capture 74 per cent of farming households.

“The question is, should we prevent it and try to do something before the damage happens?”

FINDING SOLUTIONS

While climate change mitigation and long-term water infrastructure development will ultimately be crucial to limiting the future damage to Thailand’s rice industry, Witsanu has researched many solutions to help farmers adapt to new challenges.

The sector continues to be beset by a lack of proper forecasting, information dissemination and risk mitigation. A lack of investment in agricultural technology or the encouragement of adoption of high-value crops that use less water, for example, has further contributed to Thailand’s ongoing difficulties.

A starting point, he said, is for the national government to restructure the way it gives financial support to farmers who have lost their crops due to extreme weather.

Right now, the government pays out unconditional aid in the event of drought or flood. Witsanu argues that this does not help change behaviours that could result in more sustainable and successful farming.

“What happens, for example, is if the rice dies because of the drought, they get money. That's it. And what happens next year? The government has to pay again.

“It didn't change any practices of the farmer to improve productivity or increase resilience of their production. We have competitors all around the world. If we just provide support all the time, in the future we will lose our competitiveness,” he said.

He argued that trying to incentivise and support young people to stay working on the land, empowering them with modern technology internet access in rural areas, promoting more water resources and funding the researching of new rice species would all be better uses of limited money to support the sector.

Manas the farmer is watching his own finances, knowing that the price that his rice can fetch per harvest can change based on its quality.

He tries to select the right grains at the right time but knows there are many things he cannot control.

“I love rice farming. It’s such a shame because I farm rice every year. But I will keep doing it until I cannot do it anymore.”

(CNA)

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.

(VAN) The central authorities, in early April, released a 10-year plan for rural vitalization.

(VAN) Viterra marked a significant milestone in its carbon measurement program in Argentina, called Ígaris, reaching 1 million soybean hectares measured.