May 16, 2025 | 10:34 GMT +7

May 16, 2025 | 10:34 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 16, 2025 | 10:34 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

A fishing village on Tonlé Sap.

The Mekong River, after its journey through Laos, at the end divides into many branches to create the peculiar land of Si Phan Don with more than 4,000 islands. Arriving near the capital Phnom Penh, the mother river suddenly gave birth to Tonlé Sap and then pumped its water more than 100 kilometers back up a large plain of 5 provinces Pursat, Battambang, Siem Reap, Kampong Thom and Kampong Chhnang. Cambodians call it Tonlé Sap, which means “Great Fresh River”, and Vietnamese here call it “the Sea Lake”. However it is called, it is to show the vastness and immensity of the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia.

The motorboat took the film crew of Vietnam Agriculture News to one of the many areas where Vietnamese people live on the Tonlé Sap. This was the beginning of the dry season in Cambodia, but after only a few minutes of leaving Chung Knea wharf, my eyes could only see waves and water.

The “Great Fresh River” was like a mother raising a community of many people, but Chovkimyeung, our Cambodian guide, said that the "mother" seemed to be getting more and more exhausted. Climate change plus too many hydropower construction projects in China, Laos and Cambodia were having immense impacts on Tonlé Sap Lake.

The water schedule changed, and the water level no longer followed the natural laws as it had always been. As a result, the life of river people became more and more difficult, especially for the Vietnamese community. According to data from authorities in the Kingdom of Cambodia, although changes constantly occur, there are approximately 8,000 households of Vietnamese origin living in Tonlé Sap. They live mainly in floating houses, near swamp forests or in rivers near Tonlé Sap. Some of them gather into one spot and formed a hamlet or village, while others go here and there, depending on the season of water up and down, scattered everywhere.

In the past few years, the Governments of Vietnam and the Kingdom of Cambodia have already had many drastic policies to support bringing Vietnamese people on the Tonlé Sap ashore, but it seems that there remain many difficulties.

Mr. Nguyen Van Mieu.

II.

Boating through the flooded forests, our first destination was a small temple built on a floating floor made of dozens of drums. This was the center of a Vietnamese village with 315 households, more than 2,000 people, living a floating life on the water. The custodian of the temple was Mr. Nguyen Van Mieu (61 years old). Some said his hometown was in Tay Ninh province, but he actually could not remember which commune or district. "It's been too long," he said.

Listening to the story people of previous generations told, Vietnamese in the southern region used to fish upstream of the Mekong River a long time ago. They lived on different rivers and made a living from fishing and shrimp. The boats were also their houses, constantly moving, and going up to Tonlé Sap at the end. They lived together in small hamlets, unable to return to their ancestors for the rest of their lives and met their end in the riverside forests. It was a journey with no beginning or end, a life of struggle, a story of tragedy.

Mr. Mieu's family, along with a few other households, were relatives and aunts who came here in the years after the unification of the country in Vietnam. Listening to the stories at that time, it could be seen that the fate of the Vietnamese in Tonlé Sap was painted with pain.

Between 1970 and 1975, thousands of Vietnamese in Cambodia were murdered at the hands of the government of Democratic Kampuchea. Tens of thousands of other Vietnamese were forced to return home. During the Khmer Rouge era, people of Vietnamese origin in Cambodia continued to be murdered under Pol Pot's genocide.

The documents of the Kingdom of Cambodia show that at that time, more than 170,000 people of Vietnamese origin were driven back to Vietnam by the Khmer Rouge, the number of people who stayed behind died of starvation, disease or were brutally killed by the Pol Pot genocide was also many.

Ms. Nguyen Thi Ha, whom Mr. Mieu called Aunt Tam (70 years old), still vaguely remembers being born on this lake. Her parents came here long ago and gave birth to a total of 8 children. Ms. Ha was the youngest. Their life, as she described, was "we float wherever the bubbles float". Although everyone grew up and got married, thinking that life would forever drift along the boats or floating houses, around 1975 or 1976, Ms. Ha could not remember clearly, the Khmer Rouge genocide emerged and wreaked havoc in the Land of Temples.

Her family returned to Tonlé Sap sometime in 1979 in a dinghy when the genocide had calmed down. Her parents' graves were still buried somewhere in Bato, a forest by the Lake, but no one remembered exactly where. Even Mrs. Ha herself did not expect that the trip from her homeland would last until now.

Most people in Tonlé Sap only know to fish to make ends meet.

Over the past 40 years, the lives of people like her have been all around this lake, never returning to Vietnam. At first, there were only 7-8 households, gradually becoming hamlets and villages to take care of each other. Men went to the "sea of water" to fish, women stayed at home and mended nets to take care of children, and those scenes became the motif of all villages in this place. Drums were connected to serve as the floor. A boat was both a means of transportation and a means of living, floating generation after generation. For a long time living like that could be called “peace”, but in recent years it has been “peace on a bubble”.

“Back in the day, fish and shrimp in Tonlé Sap were abundant, there were barely any signs of worries.” Mr. Mieu said that sometimes he went to prepare the net the day before leaving tomorrow, in the morning a lot of fish was already entangled and he did not bother to remove it. On every trip "to the sea of water", it was normal for a father and son to throw the net together and catch a few hundred kilos of fish. The caught fish was sold or exchanged for rice and daily necessities. Although it can't be considered affluent, it was enough to live by. However, in recent years it was no longer the case.

The reduction of fish and shrimp is one thing, but since the Cambodian Government has restricted fishing and issued regulations banning the use of fishing tools on Tonlé Sap, life has become even more difficult.

Carrying heavy emotions, Mr. Mieu started the engine and took us to the confluence of Siem Reap River and Tonlé Sap Lake.

That place used to be another Vietnamese fishing village, but after a ban on catching by using electric shocks, now there is only the vast river. No one knew where the villagers pull each other to. "We will probably meet same fate", the 60-year-old man's voice could not hide his worries. “Some families here, instead of fishing as in the past, converted to cage fish farming, but it holds little meaning. One careless action and you will be fined, not to mention one or two dead fish batches may force you to the point of selling the whole boat.”

Mr. Mieu's yellow card.

Our trip onTonlé Sap was also around the time Vietnam and the Kingdom of Cambodia continue to have meetings and discussions to jointly support the Vietnamese community in Tonlé Sap, hoping to somehow stabilize their lives. From 2018 until now the Cambodian Government has repeatedly issued policies to relocate the Vietnamese community from the lake.

Mr. Mieu showed me a yellow card, like a citizen's identity card issued by the Kingdom of Cambodia. There were also chips and codes, but the time limit was only two years. If you did not follow the procedure overdue, you would be fined 1 million riels, equivalent to approximately VND 6 million. That was all he or the adults in this floating village had. They called it “a permanent resident card for immigrant foreigners”.

Talking for a while, the man’s face swelled with emotions, and tears started to fall. That was when he held a photo of his first daughter taken on her wedding day 7 years ago. Since then, he has not had the opportunity to meet her again, only knowing by phone that she gave birth to a grandchild who is now of school age.

“Her wedding was also in the middle of this lake. There were only 2 people in the groom's family. They took a boat to pick up the bride and then the husband and wife ran away to Vietnam to live. They are probably around Dong Nai or Binh Duong, that is all I heard, but I have never been to Vietnam. I also want to go back, but without any papers, I just can’t. The other day, when a group of Vietnamese tourists came here to travel, I asked how the Vietnamese people in Tonlé Sap were arranged to live, they said that those places were often towns of reckless and stateless humans. It’s hurt hearing that.”

Mr. Mieu lifted his shirt, and wiped the tears.

Translated by Samuel Pham

(VAN) Vietnam’s TH Group officially put its high-tech fresh milk processing plant into operation in the Russian Federation, marking a historic moment as the first TH true MILK cartons were produced in Russia.

(VAN) Use of high-quality broodstock and biotechnology is regarded as the most effective approach to ensuring sustainable and economically viable shrimp aquaculture ahead of climate change and the emergence of increasingly intricate disease patterns.

(VAN) Carbon farming is a form of agricultural practices that helps absorb more greenhouse gases than it emits, through smart management of soil, crops, and livestock.

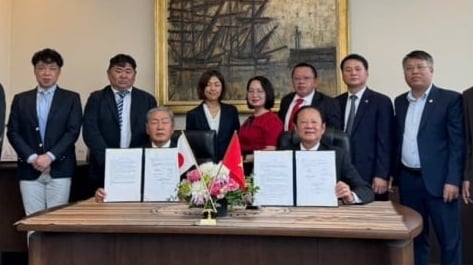

(VAN) This is a key content of the Memorandum of Understanding recently signed between the Vietnam Fisheries Society and Kunihiro Inc of Japan.

(VAN) To achieve the goal, local authorities and businesses in Kon Tum province have fully prepared the necessary conditions for the new Ngoc Linh ginseng planting season.

(VAN) Jiangsu province is gearing up to host training programs in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, this year to establish the Fish and Rice Corridor.

(VAN) Le Hoang Minh, representing Vinamilk, shared the company's experience in energy saving and green energy transition for production at a workshop held during the P4G Summit.