May 21, 2025 | 06:05 GMT +7

May 21, 2025 | 06:05 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 21, 2025 | 06:05 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Farmer Jason Lorenz holds a handful of soil from a field he farms Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021, near Little Falls. Photo: USA Today

There's still debate about just how much carbon farmers can intentionally draw from the air and deposit into the soil, a process called carbon sequestration.

Robak is working that frontier. She helps farmers change some practices and measure the impact on their soils as they join a new carbon marketplace backed by corporate partners including Land O'Lakes and General Mills.

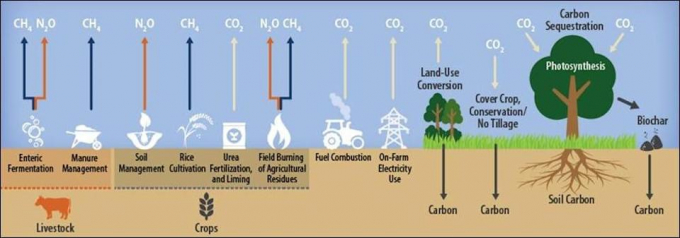

Agricultural carbon markets pay farmers to draw greenhouse gases, namely carbon dioxide, from the air and keep it locked in the soil to fight climate change. Plants do this naturally through photosynthesis; farmers encourage it by limiting their tilling, grazing livestock in crop fields and planting cover crops in the off season or between row crops.

Corporations pay for those credits through brokers to offset their carbon pollution.

By the end of August, voluntary carbon market transactions were near $750 million globally for the year, according to an Ecosystem Marketplace Insights Report, putting 2021 on track to set a new annual record since the Ecosystem Marketplace launched in 2005. The trading of greenhouse gas emissions dates back to the early 1990s, but it has accelerated this year due to a rapid increase of net-zero, carbon neutral and other climate change-related commitments from corporations.

Consumers are demanding more sustainable practices as the effects of climate change are increasingly visible and catastrophic. Countries around the world are working to meet goals set in the 2015 Paris climate agreement and keep global temperature rise this century below 1.5 degrees Celsius when compared to pre-industrial levels. That's about 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

In Minnesota, average temperatures have risen 1 degree Fahrenheit to 3 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the part of the state. Farmers are being recruited here to help combat climate change by capturing carbon, even as the science and policy of carbon markets is unsettled.

In late August, Robak stepped through a field lush with new pea shoots, kale, clover and sorghum sudangrass. All are cover crops planted as part of a pilot program that will pay farmers if their soils show a marked increase in carbon.

Farmers plant different cover crops to add nutrients to the soil, absorb excess nutrients or produce something their livestock can eat. Radishes, for example, can absorb nitrogen from the soil, which is good for water quality.

Robak, lead nutrient management specialist and certified crop advisor for Centra Sota Cooperative in Little Falls, is helping enroll producers into a carbon market pilot. The costs to make the changes are covered by the member-based nonprofit running the market called the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, or ESMC.

"Right now, in the world of carbon markets, everyone seems to have their own offer out there," said Robak. "There is no really good regulation set around it. There's no USDA farm programs around it, nothing like we have in the crop insurance world."

And there is no consensus on how to best assess soil for carbon gains.

"It's very difficult and expensive to do," said Danny Cullenward, policy director for CarbonPlan, a nonprofit that analyzes climate solutions. "That means a lot of these efforts are either trying to confront the fact that it would be very expensive to carefully measure the outcomes in these efforts or maybe they want to cut corners and find ways not to directly measure or measure cheaply."

Big companies, governments and environmental groups are willing to bet on agriculture and other working lands, like forests, to sequester excess carbon that's been released into the atmosphere primarily through combustion of fossil fuels.

Planting cover crops could sequester 6.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in Minnesota, according to a January report from The Nature Conservancy. Reducing tillage practices and improved management of fertilizers and nutrients could reduce emissions by more than 4 million metric tons.

That is the hope.

"I do think that we run the risk of really losing credibility in the eyes of the public if these markets fail. Because the hype has been so high," said Anna Cates, Minnesota's state soil health specialist. "That's where I see the greatest risk."

Related: There is a lot of money on the table with carbon markets. But farmers are skeptical.

Jen Wagner-Lahr likes that her family's Cold Spring farm will contribute data and useful information to a fledgling carbon market program.

Her husband, Larry Lahr, grows crops and raises about 450 cattle on more than 500 acres, and they're enrolled in the ESMC pilot. They planted their first cover crops this fall. They've been limiting their tilling already, a practice touted for keeping more carbon in the soil because there's less disturbance to the soil's microbiome.

"It's really kind of a unique opportunity in this region. That a pilot is here where we can actually contribute to that verification aspect," Wagner-Lahr said.

Her husband likes that there's a financial incentive to "do the right thing."

"We prefer to do our practices in a more environmentally responsible way, with sustainability in mind," Lahr said. "It's turning out we can do that without necessarily sacrificing the ability to make a living off the farm."

Jason Lorenz is another farmer in the pilot program who signed up for the soil improvements that come with practices tied to carbon sequestration and carbon markets. He’s been using cover crops to some extent for a few years and sees improvements on his farm near Little Falls. He has 40 acres enrolled in the ESMC pilot.

"It just makes your soil healthier," Lorenz said of cover crops. "You take care of the soil, the soil takes care of you."

Using cover crops brings increased yields for many farmers who try them and can bring cost savings on gasoline and fertilizer. Cover crops also help reduce erosion and allow farmland to hold more water which will make that land more resilient to the challenges that come with climate change.

The Ecosystem Services Market Consortium is halfway through a three-year pilot program. They take a soil sample when they enroll a new farm, plug it into a model and retest the soil after a few years.

Caroline Wade, ESMC deputy director, says customers are demanding legitimate climate solutions.

"The pressure is on more and more and it's consumer driven," Wade said. "Consumers want to know that the products they're purchasing have been produced sustainably and are not having negative impacts on the environment."

ESMC is making changes throughout the pilot as it gathers feedback and is trying to be thoughtful and methodical with its pilot and eventual launch, said Project Manager Stacy Cushenbery.

There's a lot of pioneering and a lot of market runners have jumped right in, Wade said. "We are working toward where we think the puck will be, not necessarily where the immediate, uncertain opportunity is."

Soil has a lot of potential to sequester carbon, but carbon test results can vary depending on the depth of the sample, where it was taken on a field and the history of land use for that particular section of earth.

The question is not whether cover crops and no-till practices draw in atmospheric carbon, but "how much can we really do," said Angelyca Jackson Hammond, manager for carbon scientific communications with Indigo, which has an agricultural carbon market program.

"We have some data, it's not perfect, but we can't wait for another 50 or 100 years until we have the perfect data set," Jackson Hammond said.

Soil health practices like using cover crops and limiting tillage have shown improvement in the structure of soil, but there isn’t a lot of evidence that they increase the amount of carbon held in it.

"We haven't found a way besides growing a prairie or growing a forest that really builds carbon," Cates said. "Farming practices can change carbon levels. And in some cases, they are just maintaining carbon levels and preventing loss, not building new carbon. Should that be a credit? You know, I don't know. That's kind of a market question more than a science question."

The very existence of the market allows big companies to continue emitting greenhouse gases while claiming those emissions are offset by agricultural or forestry practices — even while the jury is still out on whether those practices truly sequester carbon for the long term.

There's little oversight and carbon market companies often police themselves by paying third-party verifiers to back them up, which Cullenward sees as a conflict of interest.

"They all say, when you buy a credit you've caused a farmer or a forest manager to change the way that they're running their practices," he said. "They're making the claim that a small trickle of income is the difference between a project surely doing nothing good and absolutely doing something very, very positive."

The incentives are moving in the wrong direction, Cullenward said. There's pressure among carbon markets to keep prices down and provide a lot of credits.

Many agricultural activities release carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O) to the atmosphere. Some store carbon in plants and soil. Source: USA Today

Robak, the Little Falls agronomist, thinks the price for carbon should be higher. And she’s not alone.

Brad Doyle, an Arkansas farmer and vice president of the American Soybean Association, says the price needs to increase to make it worth farmers’ time and effort — whether it's private companies or governments paying the bill.

"They're not going to change their current practices with the economics such as they are with $15 (per credit)," Doyle said. "It's going to have to be $35 or more, $40 or more."

The economics need to be there, Doyle said. It is not enough to improve soil health and offer a small payment for it.

Cates sees potential in stacked benefits. Farmers could generate a credit for a positive contribution to water quality on top of a credit for sequestering some carbon, however difficult that is to measure.

"The carbon market should be the sprinkles," she said. "It should not be the primary reason that you're doing it."

Farmers are motivated to enroll for myriad reasons, and cover crops look different on every farm depending on the soil, geography and primary crop.

The bottom line is a factor for many, but not for all.

"I ain't farming to get rich. I'm farming because I like it, and that's what God put me here for, to take care of it," said Little Falls farmer Jason Lorenz. "I want to leave it better than I found it."

This story is part of a St. Cloud Times series on natural climate solutions supported by the MIT Environmental Solutions Journalism Fellowship. Journalism Fellow and St. Cloud Times Reporter Nora Hertel visited 10 farms this summer and interviewed dozens of experts on climate change, forestry, agriculture and more. Primary photography is by St. Cloud Times Photojournalist Dave Schwarz. Anna Haecherl is the project's content coach.

Visit sctimes.com for additional stories, photos, videos and podcasts featuring farmers and experts in Minnesota.

Join us Nov. 2 in person or online for a panel discussion at Milk & Honey Ciders with food from KREWE Restaurant featuring beef and honey from producers on the panel. Panelists include farmers using sustainable practices at Early Boots Farm in Sauk Centre and Lahr Heritage Acres in Cold Spring.

(USA Today)

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.

(VAN) The central authorities, in early April, released a 10-year plan for rural vitalization.