June 21, 2025 | 03:27 GMT +7

June 21, 2025 | 03:27 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 21, 2025 | 03:27 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

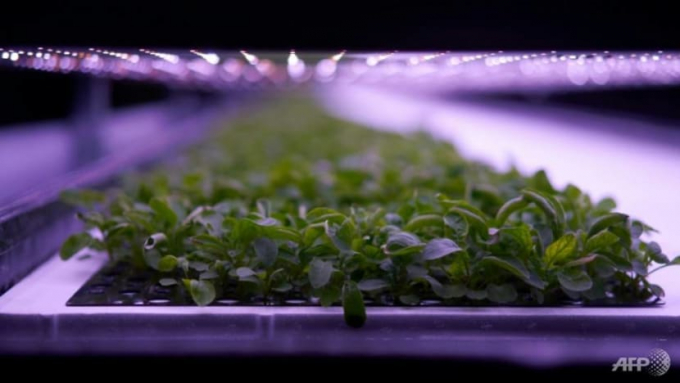

A vertical farm in a Copenhagen industrial zone. Photo: AFP

With just weeks to the crucial COP26 UN climate conference in the UK, there is a rising tide of interest in a final, unfinished piece of the Paris Climate Agreement – the rules of the game for a new generation of voluntary carbon markets.

Many nations, companies, scientists and non-government organisations see these as an accelerant towards stepped-up climate action and a way to handle currently hard-to-cut emissions.

Malaysia just announced plans to develop a domestic emissions trading scheme with environment minister Tuan Ibrahim describing it “as a catalyst for the country’s socioeconomic growth in line with (its) low-carbon development aspirations”.

After years in the doldrums, the momentum here is picking up. Voluntary carbon markets have posted a near-60 per cent increase in value over the first eight months of 2021 and are set to hit a record US$1 billion by year’s end, according to Ecosystem Marketplace.

McKinsey now estimates this trade in carbon credits could be worth upward of US$50 billion in 2030.

These market mechanisms could hold the key to bringing down the costs of highly expensive technologies that promise to capture pollution directly from the air or harvest electricity from the oceans and seas.

Voluntary carbon markets also have the potential to generate much needed funding to protect precious forests and hasten smarter and more sustainable agriculture.

But such efforts have critics who view compensating emissions or offsets as bywords for greenwashing benefitting polluters rather than the climate or communities.

Environmental group Greenpeace is among the harshest, likening the use of offsets to a “get-out-of-jail-free card” for oil, aviation and coal firms.

THE POWER OF CARBON MARKETS

Formal carbon markets emerged from the 1997 Kyoto protocol, the second UN emission reduction treaty.

Rich countries could offset emissions at lower costs by investing in clean energy, forestry projects and other green initiatives in developing countries. Voluntary carbon markets allow companies to do the same thing, broadly speaking, with carbon credits tradable on exchanges like the one in Singapore.

Formal markets are subject to government rules, such as the Californian compliance markets, whereas voluntary ones are generally managed with rules set by third-party certification bodies such as the Gold Standard and used by project developers like South Pole.

In an ideal world, we would already have decarbonised our economies, the threat of irrevocable and dangerous climate change would no longer exist, and there would be no need for offset mechanisms in the first place.

But we are not there yet. No matter how hard everyone tries, there will still be some level of pollution to be addressed in positive, creative and above all transparent ways.

Indeed, without the option of offsetting now, many experts fear it will be harder and costlier to reach net zero by 2050 and avoid emissions soaring well above 1.5 degrees Celsius safety limit.

There are many examples where high-quality carbon offset projects are showing promise as forces for good. Take Rimba Raya, a US$5 million investment in an area of forest and peatlands in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia the size of Singapore.

By some estimates, the project has over the last 10 years avoided 130 million tonnes of carbon emissions – the equivalent of taking 13 million cars off the road – while helping to meet several UN Sustainable Development Goals around jobs and education.

But there are many examples where offsetting has, it is claimed, not delivered on its promises. Indeed, environmental groups often cite a famous project in Thailand where a power company burns waste rice husks generating carbon credits sold to companies in Japan to offset their emissions.

According to Carbon Trade Watch, rice husks are a source of fertiliser for local farmers who now have to buy expensive, petroleum-based chemical fertilisers, generating more carbon pollution overall.

There have also been renewable energy projects that would have happened anyway, programmes to conserve forests too full of loopholes to be credible and others where local communities have been shortchanged.

MARKETS CAN BE TUNED TO SUPPORT ZERO-EMISSIONS RACE

With the right rules, market mechanisms can achieve high levels of integrity that can help big and small companies get onto the low-carbon, net-zero pathway at speed and at scale.

Solar panels. Photo: iStock

Two new bodies – the private-sector led Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets and its new governance body and the associated Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative – have been charged with boosting the benefits and managing the flaws.

With smart guardrails and a few more things to do, the benefits of this race-to-zero can flow not only to investors taking the risk, but also to more developing countries and communities on the ground.

First, companies must adopt science-based targets and publish plans aimed at halving emissions by 2030 and reaching net zero no later than 2050. They must decarbonise first, offset second, with a timeline for the use of fewer offsets.

Second, regulators must ensure rules on offsets are integrated with those governing reporting standards.

Third, governments must work towards a regulated, prudent price on carbon rewarding real action. We should not do this on the cheap.

Finally, markets must be transparent, liquid and global - offering the possibility of everyone, including indigenous people and the rural poor living in and working on these projects, reaping gains.

COMPANIES MOST RESPONSIBLE FOR CLIMATE CHANGE PAY SHARE OF COSTS

We need all hands on deck to meet the safety limits of the Paris Climate Agreement. Today the global average temperature rise is around 1.1 degrees Celsius and emissions into the atmosphere continue to rise.

No one is immune. Only a few months ago devastating floods ripped through homes in Germany’s Nord Rhine Westfalen region. Over 2 million in Kenya are facing drought because the rains have failed again. And in mid-July, China’s Henan province, one of the country’s most populous regions, was hit by a year’s worth of rain – 640mm – in just three days.

The frequency and scale of climate impacts are now outstripping the ability of the world’s poorest countries to cope. We must take every action possible and quickly.

If we are handed a mechanism by which the companies most responsible for causing climate change pay a share of the costs for solving it to those on the frontline, then it would be folly to ignore it.

Voluntary carbon markets are not a silver bullet, but they must be part of the suite of measures and stepped-up financial flows that help achieve the goals of the landmark Paris Climate Agreement.

Carbon markets have been part of the climate action story for over 20 years and, like Sergio Leone’s famous wild west film, littered with the good, the bad and the ugly.

As we look to November’s COP26, let’s work together with those shaping the ground rules to ensure the “bad and the ugly” of offsetting are consigned to history books in favour of those helping to deliver a climate safe world now and over the decades to come.

(AFP)

(VAN) Poultry production in Poland, which has only started recovering from devastating bird flu outbreaks earlier this year, has been hit by a series of outbreaks of Newcastle disease, with the veterinary situation deteriorating rapidly.

(VAN) Extensive licensing requirements raise concerns about intellectual property theft.

(VAN) As of Friday, a salmonella outbreak linked to a California egg producer had sickened at least 79 people. Of the infected people, 21 hospitalizations were reported, U.S. health officials said.

(VAN) With the war ongoing, many Ukrainian farmers and rural farming families face limited access to their land due to mines and lack the financial resources to purchase needed agricultural inputs.

(VAN) Vikas Rambal has quietly built a $5 billion business empire in manufacturing, property and solar, and catapulted onto the Rich List.

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.