May 18, 2025 | 02:16 GMT +7

May 18, 2025 | 02:16 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 18, 2025 | 02:16 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Source: Journal of Cannabis Research, 2021

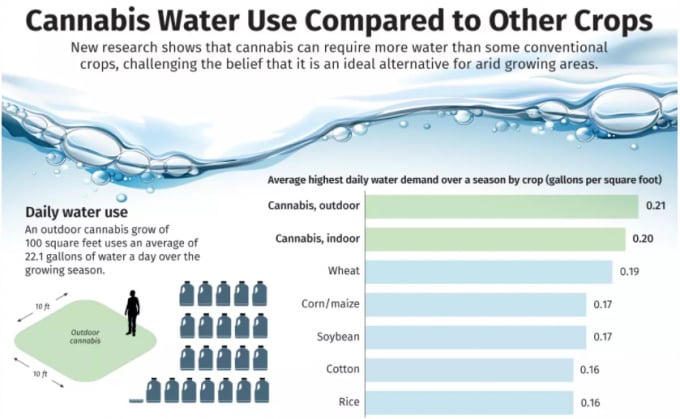

However, new research shows that’s not necessarily the case, and, in many instances, cannabis can require more water than even some conventional crops.

A study reviewing environmental impacts of cannabis cultivation shows that growing the plant in both indoor and outdoor environments is water-intensive and that the high demand for water ultimately leads to water pollution and diversion.

Three Illinois State University researchers reviewed literature about cannabis cultivation and its environmental impacts on water, air, soil, energy consumption and carbon footprint.

They found that the water demand for growing cannabis typically exceeds that of commodity crops by nearly double.

On average, the researchers found, a cannabis plant consumes an estimated 22.7 liters, or 6 gallons, of water per day during the growing season, which is typically 150 days long from June through October.

By comparison, wine grapes, which are an irrigated crop produced in the same region as many outdoor cannabis crops in Northern California, use an estimated 12.64 liters of water per day.

According to a 2019 survey in Humboldt County:

The water usage of outdoor cannabis cultivation in Northern California is 5.5 gallons per day per plant in August and 5.1 gallons per day per plant in September.

Indoor cultivation used 2.5 gallons per day per plant in August and 2.8 gallons per day per plant in September.

Irrigated agriculture in California is considered the largest water consumer, accounting for 70% to 80% of stored surface water.

As water scarcity continues to be a problem because of agricultural demands, population growth and climate change, the higher water needs for cannabis crops will challenge the marijuana and hemp industries while burdening the environment, researchers concluded.

Source: Journal of Cannabis Research, 2021

Average daily water use and needs for cannabis crops certainly will vary by growing region, soil properties, weather and cultivation types, the researchers noted, but generally, cannabis should be considered a high-use water plant.

Cannabis geneticist and breeder Brian Campbell agrees that cannabis is by no means a “miracle plant” that can be magically produced with little to no water, but it’s more complicated than that, he told MJBizDaily.

Currently a plant breeder for Charlotte’s Web in Boulder, Colorado, Campbell conducted his own research on cannabis water use while pursuing his Ph.D. at Colorado State University.

Studies to measure exactly how much water cannabis uses are still underway, but they’re highly variable because of the many different end uses for crops such as hemp, Campbell said.

“For instance, when you plant hemp for fiber, you plant it in a totally different way than you plant when you’re growing for CBD, and if you grow for oilseed, you plant in a different way and you use different varieties,” he said.

Fiber varieties can be water-intensive because the seeds can be planted closely together and then grow several feet tall for biomass, while shorter seed varieties often will finish 40 days earlier than fiber varieties.

Then there are the cannabinoid varieties, which are spaced out and less dense but grown to a larger size to maximize biomass.

“So there’s all these different crop-management styles that go along with what you’re trying to produce,” Campbell said.

That differs from the researchers’ comparisons of nonspecific, outdoor- and indoor-grown cannabis that didn’t include crop life stage, for example.

“There are massive differences in how much water you’ll use during life stages of the plants, as well as where you’re growing them,” Campbell said.

“I think that it’s a little more nuanced than one (crop) is better than the other.”

Further, there’s a big difference between just growing a crop to survive and nourishing it with water and nutrients to maximize production and perform at a high level, Campbell said.

Growing high-THC cannabis uses more water per plant because there’s a strong push in the market for quality characteristics, and restricting water can hurt some of those parameters, he added. So it might use more or less than hemp depending on how densely crops are planted as well as the size and varieties in production.

Hemp has a lot of potential to compete with crops such as corn, cotton and soybeans, but as the industrial hemp supply chain is being built out, those crops aren’t going anywhere, Campbell said.

And, like cannabis, they all perform and yield better with more water than less.

“There’s a lot of people pushing to build infrastructure and get a foothold in these (industrial) markets,” he said, but when you’re looking at the CBD market, there’s no other crop to compete with.”

Campbell added that he is optimistic about diversifying the hemp market and building that industrial infrastructure, but there’s still a long road ahead and it doesn’t do any good to have false expectations.

Marijuana and hemp are crops that will need to be managed like other crops, with rotational needs, water and fertilizer needs, he points out.

“People are still dialing that in because a lot of that basic agronomy stuff wasn’t done during prohibition when it was on every single other crop, so we’re still kind of learning where the sweet spots are,” Campbell said.

“When you’re not exactly sure how much fertilizer or water you’re going to need, you’ll tend to go a little over rather than a little under, because it will make a more productive crop and you won’t take hits on yield.”

(Mjbizdaily)

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.

(VAN) The central authorities, in early April, released a 10-year plan for rural vitalization.

(VAN) Viterra marked a significant milestone in its carbon measurement program in Argentina, called Ígaris, reaching 1 million soybean hectares measured.