February 18, 2025 | 14:35 GMT +7

February 18, 2025 | 14:35 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

February 18, 2025 | 14:35 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

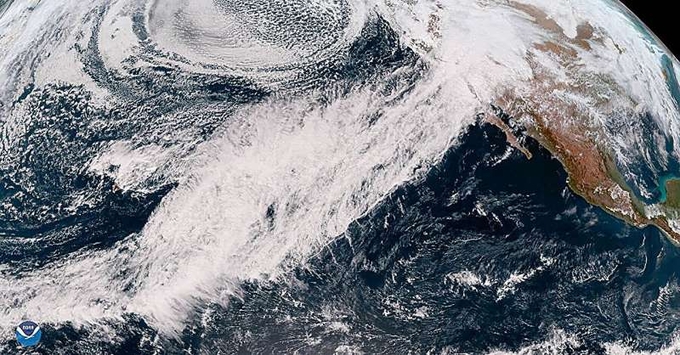

Credit: NOAA GOES-West.

El Niño and La Niña are climate phenomena that are generally associated with wetter and drier winter conditions in the Southwestern United States, respectively. In 2023, however, a La Niña year proved extremely wet in the Southwest instead of dry.

New research from scientists at UC San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography finds that atmospheric rivers explain the majority of atypical El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) years, such as 2023. For example, during 2023's La Niña, California experienced a series of nine atmospheric rivers that added up to the state's 10th wettest year on record.

The study, published in the journal Climate Dynamics, shows that atmospheric rivers can overwhelm the influence of El Niño and La Niña on annual precipitation totals in the American West. This has important implications for water managers, who rely on seasonal forecasts based on El Niño and La Niña to inform key planning decisions around reservoirs and water allocation.

Despite El Niño and La Niña's pervasive influence on global climate, atmospheric rivers don't appear to follow their lead. "Atmospheric rivers don't dance to the tune of ENSO," said Alexander Gershunov, a climate scientist at Scripps and co-author of the study.

While dancing to the beat of their own drum, atmospheric rivers are key in California's water supply, delivering on average up to 65% of the annual precipitation in Northern California and 40% in Southern California. Their contribution, however, varies greatly from year to year. For example, in Southern California, atmospheric rivers accounted for as low as 5% in 1977 and as high as 71% in 1956.

"Atmospheric rivers are the precipitation wildcards in the Western U.S.," said Rosa Luna-Niño, a postdoctoral scholar at Scripps and lead author of the study.

"One or two atmospheric rivers can turn it into a wet year, but a weak atmospheric river season can turn it into a dry year. This means we can't trust El Niño and La Niña completely to make accurate water year predictions."

Scientists expect these rivers in the sky will become increasingly important sources of annual precipitation in the Western U.S. under climate change, potentially making El Niño and La Niña years stray even further from their typical patterns.

NOAA declares an El Niño when waters in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator are anomalously warm over a three-month period. La Niña is the opposite, identified when there are colder than average water temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific.

The temperature of this patch of the tropical Pacific Ocean is closely monitored because it has far-reaching effects on atmospheric circulation and global climate.

El Niño and La Niña typically last between nine and 12 months but can sometimes stretch to multiple years. The two phenomena are useful for long-range forecasting because they can be detected months before their effects are felt.

Atmospheric rivers are ribbons of water vapor in the sky that can deliver huge amounts of precipitation when they reach land. The landfall of a brewing atmospheric river can be predicted up to three weeks in advance (Scripps scientists at the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, or CW3E, are working to improve these forecasts), but the seasonal frequency of atmospheric rivers is nearly impossible to predict.

After 2023 brought record-setting rain and snowfall despite La Niña conditions in the Pacific, the study authors wanted to know if there were other years that went against the grain of what was expected based on ENSO. Further, they wanted to explore whether atmospheric river activity was higher or lower in those anomalous years.

The team analyzed more than 70 years of weather data, comparing expected rainfall patterns based on ENSO with precipitation records. The researchers separated rainfall into two categories—precipitation from atmospheric rivers and precipitation from other sources—to isolate the contributions of atmospheric rivers.

The team's analysis revealed that roughly 32% of the ENSO years analyzed were what they termed "heretical," meaning they went against the canonical patterns of precipitation expected from El Niño and La Niña. Of those heretical years, anomalously high or low atmospheric river activity explained roughly 70% of them.

The results suggest that atmospheric rivers can override traditional El Niño/La Niña predictions. During these anomalous years, just a few powerful atmospheric rivers could transform an expected dry La Niña year into a wet one (1967, 2011, 2017 and 2023), or their absence could turn a predicted wet El Niño year into a dry spell (1964,1977, 1987, 2007, 2013 and 2015).

The findings suggest water managers in the Western U.S. cannot overly rely on El Niño or La Niña predictions for seasonal planning. Recently, CW3E at Scripps began including a disclaimer with one of its seasonal forecasts to clarify that while ENSO is the main driver of seasonal precipitation in the Western U.S., these forecasts account mostly for precipitation not associated with atmospheric rivers.

If climate change makes atmospheric rivers even more dominant contributors to yearly rainfall patterns in the future, as research suggests it will, ENSO could become even less useful for seasonal forecasting.

In the meantime, Luna-Niño said she and her co-authors are looking to merge the seasonal forecasts based on ENSO with the shorter term sub-seasonal forecasts that predict atmospheric rivers.

"We need to keep improving our ability to predict atmospheric river landfalls, and the better we get at that, the more we can use that information to help us interpret the seasonal forecast and vice versa," said Gershunov.

In addition to Luna-Niño and Gershunov of Scripps, F. Martin Ralph, Alexander Weyant, Kristen Guirguis, Michael DeFlorio and Daniel Cayan of Scripps as well as Park Williams of UCLA co-authored the study.

(Phys.org)

(VAN) The exportation of lobster, crab, and other fresh seafood to China has surged in the first month of this year due to increased demand for the Year of the Snake.

(VAN) Enhancing trade exchanges, reducing emissions in agricultural production, providing seeds, and fostering innovation are key areas of bilateral cooperation potential between the two countries.

(VAN) Discover how hornworts’ CO₂-concentrating mechanisms could boost crop efficiency by 60%, revolutionizing agriculture and combating climate change.

(VAN) Looking at the current satellite image of Dalat from Google Earth, I see the clear white patches of the greenhouse like a white towel on the green land.

(VAN) FAO Director-General addresses High-Level Side Event at African Union Summit in Addis Ababa hosted by the King of Lesotho.

/2025/02/15/2141-1-nongnghiep-172136.jpg)

(VAN) There are 1,200 stalls of more than 100 businesses from many countries and territories participating in the Quy Nhon International Outdoor Lifestyle Fair 2025 (Q-FAIR 2025).