May 20, 2025 | 13:26 GMT +7

May 20, 2025 | 13:26 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 20, 2025 | 13:26 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Humans have been reshaping the planet’s land for millennia by clearing wilderness to grow crops and raise livestock. As a result, humans have destroyed one-third of the world’s forests and two-thirds of wild grasslands since the end of the last ice age.

This has come at a huge cost to the planet’s biodiversity. In the last 50,000 years – and as humans settled in regions around the world – wild mammal biomass has declined by 85%.

Expanding agriculture has been the biggest driver of the destruction of the world’s wilderness.

This expansion of agricultural land has now come to an end. After millennia, we have passed the peak, and in recent years global agricultural land use has declined.

‘Peak agricultural land’

Agricultural land is the total of arable land that is used to grow crops, and pasture used to raise livestock.

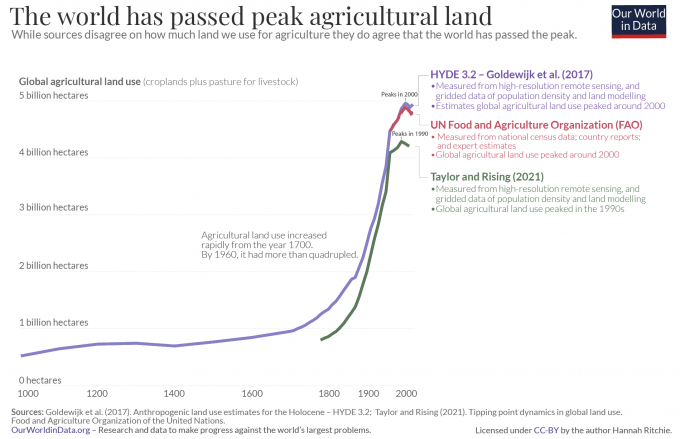

Measuring exactly how much land we use for agriculture is difficult. If all farms were simply rows of densely-planted crops it would be straightforward to calculate how much land is being used. Just draw a square around the field and calculate its area. But across much of the world, this is not how farming looks: it’s often low-density; mixed in with rural villages; in tiny smallholdings that are somewhere between a garden and a farm. Where farmland starts and ends is not always clear-cut.

As a result, there are a range of estimates for how much land is used for agriculture.

Here I have brought together the three leading analyses on the change in global land use – these are shown in the visualization.1 Each uses a different methodology, as explained in the chart. The UN FAO produces the bedrock data for each of these analyses from 1961 onwards; however, the researchers apply their own methodologies on top, and extend this series further back in time.

As you can see, they disagree on how much land is used for agriculture, and the time at which land use peaked. But they do all agree that we have passed the peak.

This marks a historic moment in humanity’s relationship to the planet; a crucial step in its protection of the world’s ecosystems.

It shows that the future of food production does not need to follow the destructive path that it did in the past. If we continue on this path we will be able to restore space for the planet’s wilderness and wildlife.

A global decoupling of agricultural land and food production

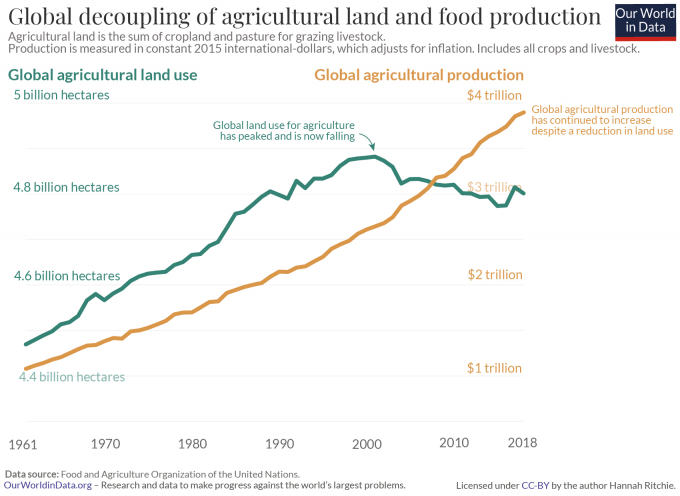

Despite this reduction in agricultural land, the world has continued to produce more food. This is true of both crops and livestock.

We see this decoupling in the chart that presents the UN FAO’s data. It shows that global agricultural land – the green line – has peaked while agricultural production – the brown line – has continued to increase strongly, even after this peak.

When we break each agricultural component out individually, or look at it in physical rather than monetary units, we find the same trend: a continued increase in output. You can explore this data for any crop or animal product in our Global Food Explorer.

This shows that feeding more people does not have to mean taking habitat away from other wildlife. This decoupling means that we can produce more while giving land back to nature at the same time.

The future of land use rests on the decisions we make today

Beneath this global picture there are a range of national patterns of land use. Many countries have passed this peak, but there are some where agricultural land is still increasing.

This is especially true of croplands, which are still expanding globally. We see this reflected in the HYDE 3.2 series in the first chart. This series reached its highest levels in the early 2000s and has declined since then, but is seeing a small rebound in recent years.

Most of the countries with expanding land use are in Sub-Saharan Africa and South America. As populations increase, and incomes rise, the pressure on land will continue.

This is why – as I argue here – improvements in crop yields, agricultural productivity, and dietary choices are so important. Fail to invest in these improvements and we risk reversing this global trend. Make it a priority, and we can accelerate reaching this peak everywhere.

The U.S. winter wheat harvest potential in Kansas has dipped by more than 25% because of severe drought, and farmers in the state may leave thousands of acres of wheat in fields this year instead of paying to harvest the grain hit by the dry winter.

But North Dakota has the opposite problem, as the area has received too much downpour. A historic April blizzard left some of the state's pothole-dotted fields under more than 3 feet of snow, causing floods as it melted.

(Ourworldindata)

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.

(VAN) The central authorities, in early April, released a 10-year plan for rural vitalization.