May 22, 2025 | 16:12 GMT +7

May 22, 2025 | 16:12 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 22, 2025 | 16:12 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

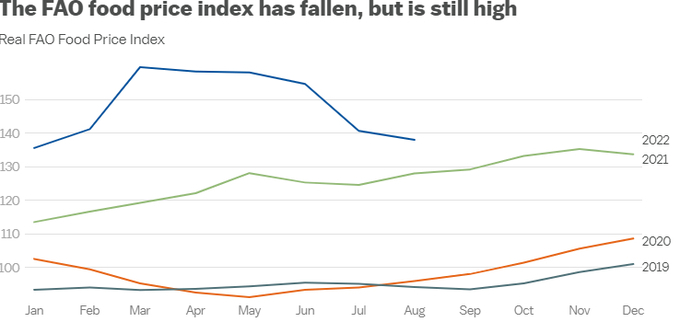

Far too many people still can’t afford the food they used to eat. Chart: Siobhan McDonough/Vox

The global inflation crisis has hit Americans’ wallets hard — but its consequences have been even graver for large swaths of the world. According to a report last month from the World Bank, food in many countries is now 10 to 30 percent more expensive than it was a year ago.

High food prices have a ripple effect on everything from nutrition and migration to conflict and even gender relations. Although food inflation rates aren’t as high as they were when the war in Ukraine started, any increase in the price of staples like wheat and oil puts the hundreds of millions of people in low-income countries who spend half their money on food at risk of hunger.

Inflation compounds a global food crisis that finds hundreds of millions of people suffering from malnourishment. Where food is most unaffordable, malnutrition is widespread, meaning people are underweight and have vitamin deficiencies, and children aren’t growing as tall as they should. Food insecurity not only affects health but also forces people to leave their homes and increases risk of conflict.

The three countries with the highest food inflation — Lebanon, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela — had already experienced hyperinflation in recent years. (Hyperinflation is commonly defined as very high inflation, typically a monthly rate of around 50 percent.) But in the last year, many other low- and middle-income countries have also experienced the twinned inflation and food crises that have plagued these three countries.

The worsening picture for food security is just one of the most consequential impacts of the global rise in prices.

We’ve seen a respite from spiraling prices — but food is still more expensive compared to a year ago

The world hunger situation is better than it was at the beginning of the war in Ukraine six months ago.

Global food prices have dropped for five consecutive months and are now back to their levels from before the war, which had precipitated a spike. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), prices fell in August in all measured categories: cereals, oil, dairy, meat, and sugar.

Over 200 million fewer people are now estimated to be food-insecure than at the beginning of the war or even the end of 2021, when food prices were at 10-year highs due to rising energy prices, weather, and an increase in global demand.

But that bit of respite is happening amid a global food situation that’s still largely dismal. International cereal prices in August were 11.4 percent higher than they were a year before, and the FAO’s food price index, which measures monthly food price changes, is overall still much higher than in recent years.

How inflation affects hunger

Most of the countries with the highest food inflation in the world, such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and Lebanon, have had uniquely high inflation for years.

Venezuela went through hyperinflation from 2017 to earlier this year, said Diego Santana Fombona, an economist at Ecoanalítica, a consultancy in Caracas. The main reason for this hyperinflation, he said, was that the government increased money supply in response to decreasing oil and tax revenue. While the government began decreasing money supply and allowing foreign currencies such as the dollar to circulate in 2019, hyperinflation persisted until the beginning of this year.

While Venezuela’s inflation has somewhat lessened in recent months, food inflation — along with inflation in other necessities such as transport and health care — is higher than overall inflation. This means that for years, people have no longer been able to afford the foods they used to. For Venezuelans living in extreme poverty, it’s been hard to maintain a nutritionally diverse diet that incorporates vegetables, cheese, and meat, said a humanitarian worker at an NGO in Caracas, who asked to remain anonymous because of their organization’s communication policy. Breads and cereals are now what people can afford to eat — but if they have the extra money, they’ll opt for protein, because “if you have a little bit of chicken and fish in your home, you are rich.”

“People are eating but not well, and they are used to not eating well,” said the NGO worker. “The food insecurity situation has been present for so many years that for many people, especially young people, this is the only thing they remember.”

This year, most of the world has begun to experience what happens when food prices spiral. Even in countries where food inflation isn’t completely out of control, it’s affecting diet and nutrition. In the US, for example, a dozen eggs that would’ve cost $1.53 in 2019 (adjusted for inflation) cost $1.67 in 2021. So unless someone’s salary has increased by the same amount in the last couple of years, food — particularly animal products — is taking more of their income.

And while people in the US spend about 10 percent of their incomes on average on food, in poorer countries this share can be as high as 50 percent, the authors of the World Bank Food Security Update told me in an email.

Preventing hunger and its ripple effects

Unaffordable food causes other problems. In addition to health and growth issues, malnutrition causes cognitive problems for young children that may affect them their whole lives. Women are more likely to be undernourished than men, and that gender gap only grew last year, adding to the burden women faced in pandemic job loss and unpaid caregiving.

In countries where people can’t pay for food for their families, they look for work in other regions or countries. This leaves them vulnerable to human trafficking, while leaving their children can be traumatic for families. Famine also forces people from their homes.

“We need humanitarian aid going to countries that are most in need,” said Marco Sanchez Cantillo, co-author of the FAO’s 2022 food security and nutrition report. To prevent hunger and prepare for shocks in the long run, said Sanchez Cantillo, governments will need to address more structural factors to make food systems more sustainable: for example, reducing food waste, building rural roads, and supporting more nutritionally diverse foods.

The authors of the World Bank report said that in addition to taking steps to make fertilizers more affordable and available, governments can set aside trade restrictions, avoid stockpiling food, and provide cash transfers to vulnerable households.

Global hunger has been going in the right direction for a few months, but the inflationary environment is still a cause for concern. Hundreds of millions of people can’t afford the food they could pre-pandemic, and it’s the poorest people around the world who continue to be hit the hardest.

(Vox)

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.

(VAN) The central authorities, in early April, released a 10-year plan for rural vitalization.