May 28, 2025 | 01:43 GMT +7

May 28, 2025 | 01:43 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 28, 2025 | 01:43 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

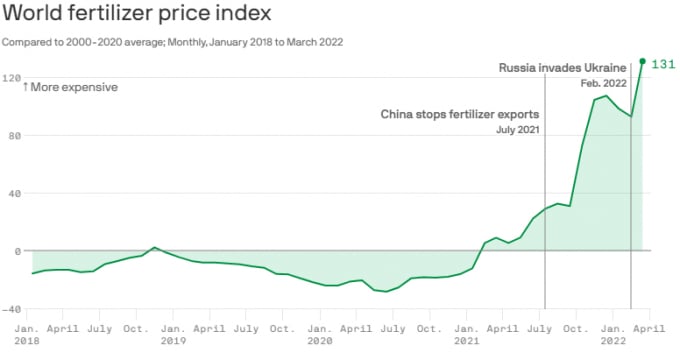

Data: International Food Policy Research Institute, NPK prices; Chart: Axios Visuals

Why it matters: Skyrocketing fertilizer costs — like those made from nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK) — are driving up food prices and, worse, threatening food security around the globe.

State of play: Prices for NPK were up 125% in January from a year before, and rose another 17% from the beginning of the year to March, according to data compiled by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

The looming European ban on Russian natural gas (a critical component in manufacturing some fertilizers) could worsen the situation.

"We're in a dire situation right now," said Svein Tore Holsether, the CEO of fertilizer maker Yara International, at a seminar hosted by IFPRI this week.

If farmers use less fertilizer, they can't produce as many crops — and that raises the specter of "malnutrition, political unrest and, ultimately, the otherwise avoidable loss of human life," Bloomberg reported.

The big picture: Prices for these heavily traded raw materials were already rising in 2021, because of a myriad of factors: Hurricane Ida in the U.S., an upsurge in demand after the pandemic, supply chain issues, and rising natural gas prices that predated the war in Ukraine.

Then, two things made that worse:

China: The country, which supplies 24% of the world's phosphates, 13% of nitrogen and 2% potash, halted fertilizer exports this past summer.

War: Russia's invasion of Ukraine disrupted trading in the Black sea, putting the global food supply in peril generally (for instance, the wheat disruption). Russia and its ally Belarus also produce a lot of fertilizer. In 2020, Russia provided 14% of urea (a nitrogen fertilizer), and, with Belarus, 41% of potash, a potassium fertilizer.

Of note: Fertilizer is a heavily traded product, meaning most countries — even the ones making lots of food — import their supply.

Three-quarters of countries in the world depend on imported fertilizer for 50% or more of their fertilizer use, IFPR notes.

Some countries, including Mongolia, Nicaragua and Ecuador are at the mercy of Russian and Chinese policies with the majority of their fertilizer supply cut off.

The bottom line: In richer countries, we'll continue to see higher food prices, and in more vulnerable countries things could grow desperate.

"Many fields are not being planted," Theo de Jager, the president of the World Farmers' Organisation, said yesterday. "I"m not so sure it's possible to avoid a food crisis."

"Farmers need peace," de Jager said.

Rising fertilizer prices highlight science of healthy soil

Skyrocketing fertilizer prices are renewing focus on other tools that could ultimately improve the health of soil and strengthen food production.

Why it matters: Shocks to the world's agriculture systems — including droughts fueled by climate change, as well as seed and fertilizer shortages due to conflicts and natural disasters — are likely to become more frequent.

Driving the news: The price of fertilizer has climbed around the world, pushing some farmers to apply less nitrogen, phosphorus and potash to their crops, Bloomberg reports.

Reduced fertilizer use is threatening crop yields and quality — and global supplies of already increasingly costly food that could hit particularly hard for people in the world's poorer countries.

What's happening: In the U.S., rising fertilizer prices may be motivating some farmers to test plant- or microbe-based biological fertilizers being developed by a slew of startups, the WSJ reports.

Farmers may also take another look at new digital agriculture tools to help them use fertilizer and other resources more precisely, says Harold van Es, a professor of soil and water management at Cornell University.

"One of the things about fertilizer being cheap, easy to apply and so effective, is that it has been used inefficiently," says Jason Kaye, a professor of soil biogeochemistry at Penn State University.

In the near term, alternative fertilizers, cover crops and digital tools could be used to reduce and optimize the use of synthetic fertilizer, which comes with environmental costs, including run off of nitrogen into rivers and aquifers.

Over time, they could help to accumulate nutrients in the soil, improving its health and buffering crops from disruptions, Kaye says.

Details: Regenerative and circular agriculture approaches focus on restoring soil health and recycling and upcycling the resources required for producing food.

The science underlying them progressed over decades as the tools of genetics, biology and chemistry became more sophisticated and less expensive — and people became more interested in the systems that produce their food.

At the University of Minnesota, researchers led by Donald Wyse are developing more than a dozen cover crop plants that can be grown when fields in the upper midwestern U.S. would otherwise sit bare, the NYT's Jonathan Kauffman wrote this week in a profile of Wyse. Those "evergreen crops" can provide farmers with another source of income and soil with organic matter and carbon.

In Uganda and Kenya, smallholder farmers are experimenting with using by-products from rice farming — including biochar made from rice husks — to try to improve the health of soil and crop resistance to disease.

Scientists at Penn State University are looking at whether composted urban food waste combined with animal manure could help reduce the amount of fertilizer needed for crops. Preliminary modeling data of croplands in the Chesapeake Bay region suggests it could without impacting water quality, Kaye says.

Washington-based Tidal Vision is experimenting with upcycling discarded crab shells to improve crop production.

But, but, but ... Designing agriculture around ecology carries uncertainties for farmers and food supplies.

Nutrients are supplied by the decomposition of cover crop plants and manure — a process that depends on microorganisms, the water available in the soil and soil temperature.

Those processes are harder to predict than taking a known amount of fertilizer and determining how much nitrogen a field will get, Kaye says.

He's developing tools to fill that "science gap" by predicting how much of a nutrient a plant or manure will deliver, which would help reduce the uncertainty for farmers.

A better understanding of soil health is emerging as scientists shift from focusing exclusively on the chemicals in soil to incorporating biology and physics as well, says van Es.

He and others are honing assessments of the indicators in soil that signal its health — a mix of organic matter, how compacted it is, the microbiome of the soil and more.

In a recent preprint paper, van Es and his colleagues identified bacterial indicators of soil health, based on genetic sequencing.

"It is still relatively new," he says, comparing soil health to human health. "Forty years ago we didn't have our good and bad cholesterol measured on a routine basis."

The catch: Adopting new tools means taking on new costs. The price points matter for farmers, especially those raising food for their own consumption rather than for market.

And, "these systems take a long time to implement. Once you do, they are resilient to shocks," Kaye says. "But they aren’t going to help us next year. It takes a decade to build soil organic matter like that."

(axios)

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.