May 18, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

May 18, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 18, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Mechanized operations for rice, from tillage, seeding... to harvesting and post-harvest, are described mainly from year 2000 to date, and focused in the Mekong Delta (MRD) which produces more than half of rice in Viet Nam, and with highest mechanization level in the country. Mechanization in other agricultural regions and Viet Nam is briefly mentioned; and in each operation, the mechanization status of to 2000 is summarized, extracted from two references (Nguyen Van Luat et all 2011; Tran Van Dat et al 2010).

Up to 2005, Viet Nam had 310 000 tractors, of with 3/4 are two-wheel machines under 15 HP; total power was about 3.5 million HP.

In 2012, total power for rice cultivation was 9.0 million HP, or 2.2 HP/hectare of rice land. These tractors resolved 67% of tillage work for the whole country; in particular, MRD got more than 92% mechanized land preparation. Tillage as heaviest farm operation incurs only 4% of total rice production cost.

To date (2023) the MRD achieves almost 100% mechanized tillage, of which about 2% by two-wheel tractors in rice-shrimp farms; Tractors of 45-60 HP are also used in the dry season; in general there is not much change in the past 20 years.

Machines work more efficiently on rice fields which are pretty large and leveled (surface differential of less than 3 cm) to keep a uniform water level. Laser leveling (LLL, laser-controlled land leveling) was transferred to Viet Nam by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 2004 (Figure 1). To date, about 3 000 ha of rice fields in the MRD have been laser-leveled, of which 2 000 ha in Long an Province; and 50 ha in Lam-Dong and Dak-Lak Provinces, merging 300-m2 plots into a 0.5-ha field.

A summary of benefits from LLL, as mentioned in different survey reports: ·Saving of water by 50%, or a decrease of 20 Liter diesel/ha for pumping. ·Decrease of 40 kg/ha urea and 40 kg DAP/ha fertilizers. ·Decrease of 2 kg of herbicides, or a cost saving of 50%. ·Decrease of 50% golden-snail pesticides if tiny plots of 0.03 ha are pooled into 0.5-1 ha, due to less levee areas for snails’ shelter. ● Saving of 20-40 kg/ha sown seed (say, from 150 kg/ha down to 110 kg/ha), and saving of 7-10 labor-day/ha for re-planting missed seedlings at low spots. ●More resistance to lodging; this reduces post-harvest losses with combine-harvesters, and a saving of 2 Liter diesel/ha operating with upright plants. ●Increase of rice yield by 0.5-1.0 ton[1] per hectare. ·Profit increase by US$260 /ha/season, consisting of $54 from yield increase, and $106 from reductions of input costs (from interviews of 16 farmer households in Bac-Lieu and An-Giang 2011).

Note two other benefits:

From 2000 several manufacturers made hand-drawn drum row seeders, using plastic materials to replace steel in the original 1990 IRRI design; plastics reduced the weight by one half compared to the 12 kg steel model. Estimates in 2006, the country had 50,000 row seeders, and used on 15% of rice field in the MRD. Due to its low labor productivity --sowing about 0.5 ha/man-day—MRD farmers up to 2020 mainly practiced broadcast seeding, in spite of spending paddy seeds at 2-3 times more than necessary. Reason is very fast operation; a knapsack sprayer can be uses to broadcast 8 hectares per day.

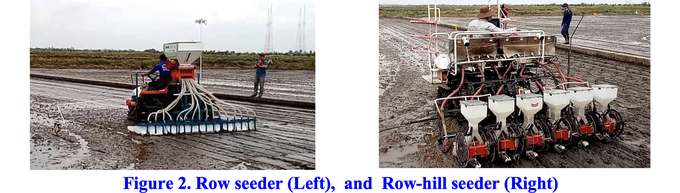

From 2020 a technological advance has been applied, namely mechanized row seeding and row-hill seeding; seeders with 8-20 rows can complete 5-10 hectares per day (Figure 2).

Seeding in rows is precise with less seeds (only50-70 kg/ha compared to 120-180 kg/ha with broadcast seeding), improves plant health with reduced pest risks, thus decreases the use of pesticides. It also reduces lodged plants thus decreases harvesting losses. The operation can be combined with fertilizer application at 3-4 cm deep. Up to 2023. these row seeders have been demonstrated/ applied on about 5 000 ha in most MRD Provinces, and about 1000 ha in other Provinces such as Thừa Thien, Binh Đinh, Ha Tinh, Hung Yen, Thai Binh, Thanh Hoa etc (Ngo Van Day 2023, personal communication).

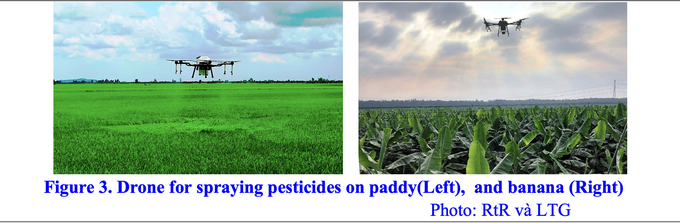

Drones were first tested in Viet Nam in 2017, with an imported equipment from Japan. From 2020, Loc-Troi Group (LTG) has expanded the use of drones (Figure 3); by the end of 2021, LTG had 120 imported drone and 220 operators (“pilot”) and sprayed about 90 000 hectares on several crops, such as rice, corn, peanut, fruit trees (banana, coconut, mango etc). Presently (2023) there are some thousands of drones (owned by companies or individuals) operating in the MRD. Besides spraying pesticides, drones can be used for applying fertilizers or seed broadcasting (not recommended, against row seeding). In the future, there would be some thousands hundreds of drones, which help in saving pesticide costs, in protecting farmers’ health and protecting the environment.

The local manufacture of drone is spearheaded by a Vietnamese Company, Real-time Robotics (RtR) in Ho Chi Minh City; they have supplied drones for remote sensing work, or for diagnostic tests of solar PV panels. Viet Nam is probably only 3 years behind other countries in terms of drone application; yet more research is needed for efficient use of drones. Like other equipment, the application technology is even more important than the equipment itself.

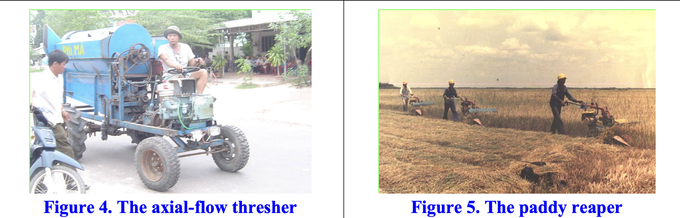

The IRRI axial-flow thresher was first tested in the MRD in 1974, and was modified by farmer-mechanics into a distinctive Viet Namese model (Figure 4), and introduced in Northern Provinces in 1990’s. It is estimated that in 2005, there were 100 000 units throughout Viet Nam; and almost 100% of paddy in the MRD as well as the Red River Delta were threshed by this type of thresher. But from 2008, the number of threshers declined and almost disappeared in 2015 as they were replaced by combine-harvesters.

About 40 years ago, all rice plants were manually cut. In 1984, the IRRI paddy reaper was tested by NLU (Nong-Lam University Ho Chi Minh City, formerly University of Agriculture and Forestry) and promoted to Long-An Mechanical Company, which fabricated 150 units up to 1988 (Figure 5). From 2000 to 2006, three other manufacturers sold a total of about 1 800 units, of which 1 300 units were in Long-An Province. The number increased to 3 500 units in 2013, reaping 10% of rice in the MRD; and then decreased and practically disappeared in 2015-2016, also displaced by combine-harvesters.

From 1975, several combine-harvesters (CBH), either imported or locally made, were tested but failed due to their heavy weight on soft soils.

In 2003 the PhilRice mini-combine was tested by NLU and the design was transfered to Vinappro Company in Dong Nai Province. The machine weighed 600 kg and was powered by a 16-HP gasoline engine or a 12-HP diesel engine, and equipped with a 1.3-m cutter bar. It could harvest 0.9-1.5 ha/day; .Total harvesting losses were less than 2% (Figure 6). From 2004 to 2009, Vinappro produced 500 units, each at a sale price of US$4 000, two other manufacturers produced a total of 900 units. But subsequently newly developed combines with higher-capacity rubber-track CBH led to reduced market demand and a phasing out of the mini-combine around 2014.

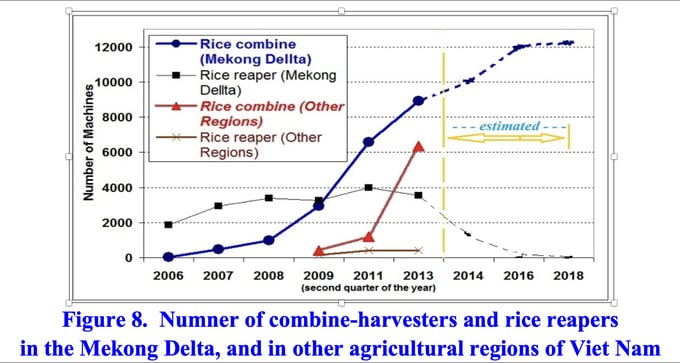

The rubber-track combine-harvesters increased rapidly with five combine contests from 2006 to 2011, organized by the Vietnamese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD); each contest involved 10-12 CHB models (Figure 7). Rubber tracks exerted a ground pressure of 22-25 kPa and could bear a heavy CBH mass of 1.7-2.7 ton. CBH cutting widths were mainly 1.5-2.0 m, with field capacities of 3-6 ha/day, with diesel consumption of 18-25 Liter/ha. Total losses were under 2% in cutting upright plants. These CBH could harvest lodged crop at the expenses of lower field capacity, higher fuel consumption, and higher losses up to 10%; which were accepted by farmers-clients on the small portion of lodged areas, since manual labor is no longer available or is very expensive. Farmers paid an average CBH fee of US $100 /ha, which was cheaper compared to US $140 /ha for manual cutting and mechanical threshing. For the combine owner, the machine had a payback period of less than 2 years. This explained the fast increase in combines in six years from 2006 to 2013 (Figure 8).

An emerging problem during this period was the machine’s reliability. Local, manually made CBH were prone to frequent brekdowns; spare parts were not interchangeable for repair, which delayed the harvesting. Thus the Japanese Kubota entered the scene and quickly dominated the market; in 2014, about 85% of CBH came from this company. They modified/improved the machine from observing good features in the above contests; and with their excellent manufacturing technology, the CBH’s reliability was ensured.

To date (2023) 98% of rice fields in the MRD and about 80% in other regions of Viet Nam are harvested with CBH.

Paddy drying became an issue in Mekong Delta in early 1980’s when a second crop was promoted, and post-harvest loss for the harvest fell during the rainy season may be as high as 40%; . Drying research at Nong-Lam University NLU came out with the 2-ton/batch flat-bed dryer (FBD) in1983, and the 8-ton dryer at Ke-Sach Seed Station (Soc-Trang Province), and with the improved reversible-air flat-bed dryers in 1994-1997, which resulted in more uniformly dried grain and less contamination of ash and dust. Farmer-mechanics replicated or modified these FBDs using cheap local materials, and actively contributed to the rapid increase of FBD in the MRD.

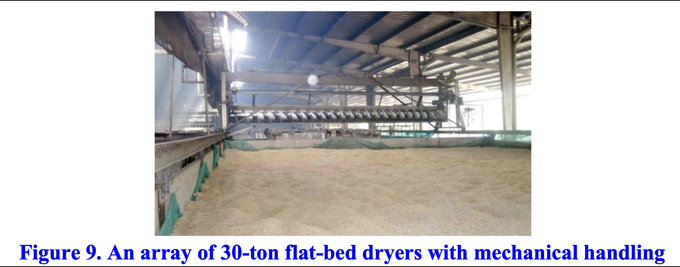

Surveys showed that in the MRD the number of FBD reached about 300 units in 1990, 1 500 units in 1997 (mainly of 4 ton/batch capacity), 3000 units in 2002, and 6 000 units in 2006 (8-15 ton/batch), of which 200 units were reversible-air models. The rate of increase has since slowed down with a total of about 9,000 units by 2013. But the batch capacity has increased to 20-50 ton, and machines include equipment for loading and unloading the grain (Figure 9). From 2018, there were “Drying centers” with bins arranged in parallel, and each system could dry 1 000-2 000 ton of paddy/day. Nowadays (2023) 98% of paddy in the Mekong Delta are mechanically dried for both wet and dry season harvests (the sun-dried 2% are mostly from rice-shrimp farms). All dryers use rice husk as a cheap fuel, so the drying fee is as low as 2.5% of paddy value.

One main drawback of FBD is non-uniformity of the grain final moisture content (MC), the differential may be 3%. This was partly remedied by new large FBD versions, which used the same unloading auger for mixing the upper 25-cm grain layer (Figure 9), thus reduced the final MC down to about 1.5%

For the other agricultural regions of Viet Nam, the share of mechanical drying is 50% or less (Phan H.Hien 2022).

Slow increase of column dryers was due to both technical and economic issues, such as inability to handle hi-moisture paddy, high drying cost, frequent breakdown, etc. Only from 2004 that some column dryers did operate smoothly thanls to various improvements such as drying high MC paddy, use of rice husk to lower the operation cost etc. Column dryers offer advantages such as saving of manual labor, and uniform final MC (differential of 0.5%, compared to 1.5% or more with flat-bed dryers) so up to 2020 the number of column dryers reached about 100 units. The drawback is still economic: both the investment and drying cost per ton of these machines are at least twice compared to flat-bed dryers. This explained the slow development of column dryers in the MRD, although these are modern equipment as used in many advanced countries.

Years ago, paddy storage was mainly at farmers’ households. Rice-exporting companies did not store paddy, even some were equipped with silo systems following French ot Japanese technologies. These silos were not efficiently used or left empty; reasons were inappropriate equipment components, and state companies mainly purchased brown rice from small rice millers in surrounding areas, for whitening and polishing rice and export...

From 2000, several private companies in the MRD entered rice export market and improved the quality of processed rice with investments in silos, which were estimated at a total of about 200 000-ton storage capacity. This number was still modest as it did not meet the storage requirement for export, which should be about 4 million ton of paddy, and be mechanized with loading-unloading and aeration equipment, and temperature control. Much needed is more research and investment in this link of the rice value chain.

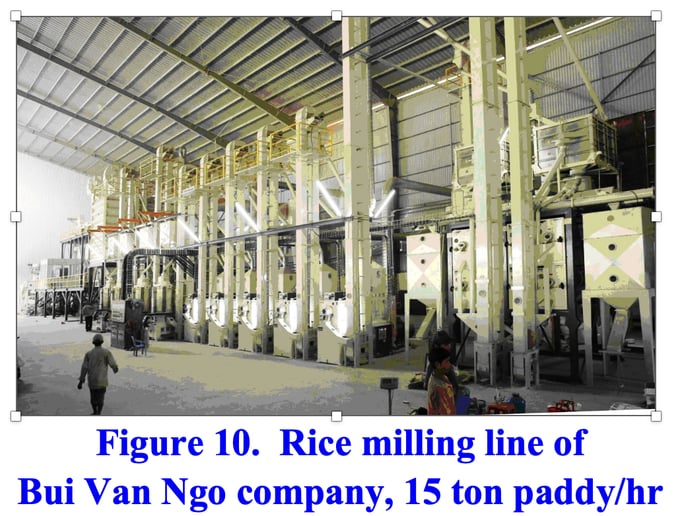

The rice milling equipment (Figure 10) is produced mainly by two companies, namely Bui Van Ngo in Ho Chi Minh City and Lamico in Long-An Province; they have exported the rice processing machines to over 20 countries worldwide. The equipment is reliable and fit for rice varieties grown in Viet Nam, and can result in a head rice yield of 52% or more, conforming to USDA or TCVN standards.

The rice milling technology has been much improved. Until about 20 years ago, rice milling in Viet Nam followed the “two-stage process”. Meaning, small rice millers husked paddy into brown rice, and waited to sell it to big companies when the latter got the export contract, they polished and re-dried milled rice. This process took weeks thus deteriorated rice quality by decreasing the head rice yield (HRY) say from 52% down to 42%, which corresponded to a 10% decrease of product value. This may be called a “reverse process”, in which milled rice is re-dried, and contrasted to “one-stage process” wherein dried paddy transforms straight into milled rice in a few hours. In fact, during that period, local people consumed the “one-satge process” rice, with better quality and higher price than exported rice.

About 2010, private companies entered the rice export market; they followed the one-stage process, thus increased the HRY to 46% or more; now it is estimated that only about 1/6 of paddy quantity is still processed by the “two-stage process”.

Improvements of rice milling technology rely on 2 other advances: a) The moisture content of dried grain is more uniform; and b) Rice varieties are also more uniform, it is hardly seen several varieties in one drying batch as previously. Hence, milled rice from Viet Nam could enter quality market, with prices almost equal or slightly higher than Thailand’s rice (unlike two decades ago, our rice price was much lower). In turn, export companies can buy paddy from farmers with more reasonable price, thus farmers are less disadvantaged in selling paddy...

Besides paddy and milled rice as main products, rice husk and straw are by-products (not wastes) from the rice plant; these have economic value if processed and used with mechanical means.

Rice husk. The annual paddy production of 43 million ton corresponds to about 8,5 million ton of rice husk, 55% of which are in the MRD (GSO 2023). In the 1995-2008 period, rice husk was a waste, given as free at US$10/ton, which is the transportation cost from the rice mill to the utilization site such as btick kilns. About 20-25% of husk quantity were dumped as wastes.

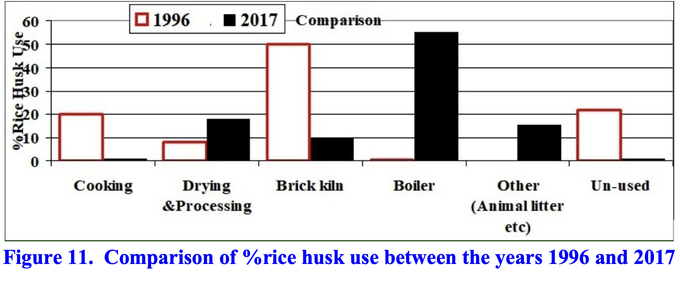

However, from 2010, new uses of rice husk pushed up its price, and stabilized in 2015-2020 at US$45/ton, which has been about one-forth of paddy price. The distribution of rice husk uses has changes notably (Figure 11); more than 50% of rice husk are burned in industrial heat-generating boilers for food processing, as a fuel substitube for coal.

Straw. the MRD produces 24 million ton paddy a year, meaning also about a same quantity of straw, which has traditionally mostly been burned off in situ, for clearing fields to prepare for the next crop; lesser amounts were incorporated into the soil or used for cattle feed and mushroom production About 10-15 years ago, straw from paddy threshers were piled up in fields or yards, which was easily gathered for feeding cattle or cultivating mushroom. Straw from one hectare of rice can be used to grow mushroom and can harvest an average of 250 kg mushroom within one month; the income is 15-20% compared to the income from selling paddy.

Between 2009 and 2013, as the harvesting of rice shifted from threshers to combine harvesters, straw was scattered in fields, and gathering it required considerable labor. At this time mushroom growers in An-Giang Province had to pay up to eight times more than previously for the straw, which led to a sharp decline in mushroom production, from 35 000 ton down to 4 000 ton/year. The in-field burning of straw increased up to 90%, which was a wastage of nutrients and a cause of polliting greenhouse gases GHG (presently, the in-situ straw burning is still about 50%).

In 2013 the introduction of straw balers facilitated the easy collection of straw from combine harvesting. From 2014 Phan-Tan company in Dong-Thap Province fabricated self-propelled balers and to date has sold about 2 500 units. We estimate that in 2016 there were about 2 600 units; and in 2023 the number reached more than 6 000 units, of which two-thirds were made by 4 local manufacturers.

These balers produce 13-15 kg, 0.5 m diameter x 0.7 m height bales from 15 percent “dry straw” with 15% MC (moisture content). Bales of very wet straw with 70% MC typically weigh 50 kg.

There are two types of balers: a) Semi-mounted behind a 20-30 HP tractor (Figure 12); mass 350-400 kg; low-cost, priced at US$2000-4000 in 2023. It ejects bales in-situ, thus needing additional labor to collect the bales. As tractor tyres lead the way, in muddy fields the bales are dirty with mud. b) Self-propelled on rubber tracks, with a platform that holds about 30 bales (Figures 13); machine mass about 2 tons; priced at about US$12000. In muddy fields the bales are kept clean as the baling component is up front.

The baling cost by machines was between 650-900 VND/kg (monetary value of 2015) depending on the equipment and on the cost of straw paid to farmer-grower, which was 100-300 VND/kg. These did not count the transportation of bales to the utilization site.

Straw balers have considerably reduced the straw percentage of field burning in the MRD. For example, Tien-Giang Province which used to have 50% field burning, but since 2016 this burning was rarely seen.

Collected straw is convenient for use in growing mushroom or feeding cattle, Another use is to mix the straw (either raw or after mushroom) with cattle manure to produce organic fertilizer. Different compost mixers (Figure 14) are available, with mixing capacities from 30 to 80 ton/hour.

In July 2023 the Department of Crop Production (MARD) issued the Decision “Procedure for straw management towards circular agriculture and low emissions in the Mekong Delta” with an attached Guide Manual, based on research results of IRRI at the MRD; the Manual includes description of related equipment. This is the cornerstone for extending the use of straw on a large scale in the MRD.

Mechanization has actively contributed to the rice value chain, especially in the Mekong Delta, and helped Viet Nam to export rice at the top rank in the world. We can be proud of these achievements; some other countries with similar climate, with good scientists and hard-working farmers, but probably lacking of mechanization, so shortage of grain food persists... Proud, but we need to look squarely at the current drawbacks and shortcomings in mechanization, so that our rice production shall be at a larger scale, with more automation, and shall be more circular and ecological. Concurrently, experiences in rice mechanization should be adapted for upland crops.

GSO (General Statistics Office of Viet Nam). 2023. Data: Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery. https://www.gso.gov.vn/nong-lam-nghiep-va-thuy-san/

Nguyen Van Luat (Editor). 2011. The rice plant in Viet Nam.. Part XI, Chapter 1: Phan Hieu Hien. Mechanization of rice production in the Mekong Delta (in Vietnamese). Agricultural Publising House, Ha-Noi.

Phan Hieu Hien. 2019. Mechanization of paddy harvesting and rice straw baling in the Mekong Delta of Viet Nam. Proceedings of the Traveling Seminar on “Mechanized Grain Harvesting for Smallholder Farmers in Nepal and Asia”. 25-29 March, 2019.

Phan Hieu Hien, Nguyen V. Hung, and M. Gummert. 2021. Good Engineering Practice: Installation, operation, performance evaluation of laser-controlled equipment in Viet Nam and related benefits. Report to the International Rice Research Institute.

Phan Hieu Hien. 2022. Rice sector - food loss scoping assessment. Report to “IFC Viet Nam Food Safety & Food Loss Project”.

Tran Van Dat (Editor). 2010. Development of Vietnamese agriculture in the 21st century. Chapter 11: Phan Hieu Hien. Mechanization and post-harvest technology in Viet Nam. (in Vietnamese). Agricultural Publising House, Ha-Noi.

Nong - Lam University Ho Chi Minh City

(VAN) Hue City rigorously enforces regulations regarding marine fishing and resource exploitation, with a particular emphasis on the monitoring of fishing vessels to prevent illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

(VAN) Hanoi People's Committee has issued a plan on reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the waste management sector with 2030 vision.

(VAN) Vietnam's draft amendment to Decree No. 156 proposes a mechanism for medicinal herb farming under forest canopies, linking economic development to population retention and the sustainable protection and development of forests.

(VAN) In reality, many craft village models combined with tourism in Son La have proven effective, bringing significant economic benefits to rural communities.

(VAN) The international conference titled Carbon Market: International experiences and recommendations for Vietnam was successfully held recently in Ho Chi Minh City.

(VAN) According to the Project on rearranging provincial and communal administrative units, in 2025, the country will have 34 provinces/cities, 3,321 communes, wards, and special zones, and no district-level organization.

(VAN) The vice president of fertilizer with Stone X Group says the Trump administration’s tariffs are impacting fertilizer markets.