July 1, 2025 | 08:20 GMT +7

July 1, 2025 | 08:20 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

July 1, 2025 | 08:20 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Vietnam is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war and the country’s reunification. Way back, on April 30, 1975, the country embarked upon a new challenging journey toward reconstruction and socio-economic development. As the backbone of Vietnam’s economy, its agricultural sector had to feed a population that doubled over five decades, reaching 100 million in 2023. An accomplishment that can provide inspiration and lessons learnt for other nations that face similar challenges. This article aims to review some experiences related to agricultural reform and development in Vietnam during the period 1975-2025.

After the war, Vietnam followed a path toward reconstruction and socio-economic development. Photo: Archive.

The transition from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy was much less smooth than hoped. The country was lacking almost everything after the war and experienced severe food shortages. Vietnam’s predominantly agricultural economy had been devastated by 30 consecutive years of armed conflict. The country’s recovery was further complicated by global geopolitics, including the 1975-1994 US-imposed embargo, the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, and the associated dissolution of the Socialist Bloc, which had been Vietnam’s lifeline for decades.

To advance its post-war development, Vietnam adopted a centrally planned economy. Despite the great effort, agricultural development stagnated and domestic food output proved insufficient to meet national demand. To feed the nation, the country initially had to import 1-2 million ton of food per year. Farmers’ earnings were meager and most of Vietnam’s rural population lived in poverty. To grow sufficient food, farmers further encroached upon Vietnam’s forestland, which was already scarred. As a result, national forest cover had shrunk to 27% in 1990.

In 1986, the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam initiated a comprehensive economic reform, called "Doi Moi", which began with the agricultural sector. Under "Doi Moi", Vietnam’s agriculture was transformed from a centrally planned, state-controlled system to a more liberal, market-oriented sector.

This was achieved through eight mutually enforcing levers:

1) Land reform, in which farmland was redistributed to millions of farmers, land taxes were waved for smallholders, and land tenure security certificates were granted;

2) Market liberalization and international integration, in which free inter-country movement of agri-food produce was encouraged and the nation became progressively integrated into the world market. Vietnam became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2007. In the meantime, seventeen Free Trade Agreements were signed with other countries;

3) Far-reaching reform of state enterprises and cooperatives, aimed at promoting private sector engagement and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI);

4) Farmer-oriented public extension backed by robust food crop breeding, phytosanitary or veterinary services and a strengthened agricultural research apparatus;

5) An extensive credit system enabling investments by agri-businesses and individual farmers alike;

6) An upgraded rural infrastructure, involving near-total coverage of (rice) irrigation, electrification and paved roadways, and targeted stimuli for supply chains and processing industries;

7) Enhanced market connections, with agri-food producers steadily moving from self-sufficiency to market-oriented production of high-value crops;

8) A bundle of enabling policies and targeted investments through government budgets, international development banks, bilateral donors and FDI;

In the subsequent decades, nutrient-dense food became readily available and affordable for all. Farmer incomes also rose steadily, poverty declined by 1-2% per annum and life expectancy rose by 10 years over 1990-2023. By generating employment opportunities on- and off-farm, Vietnam lifted 30 million people out of poverty. Added attention was given to forest protection and afforestation. By 2023, forest coverage had rebounded to 42%. As such, Vietnam’s agriculture sector became an engine for the country’s economic development, social stability and incipient environmental protection.

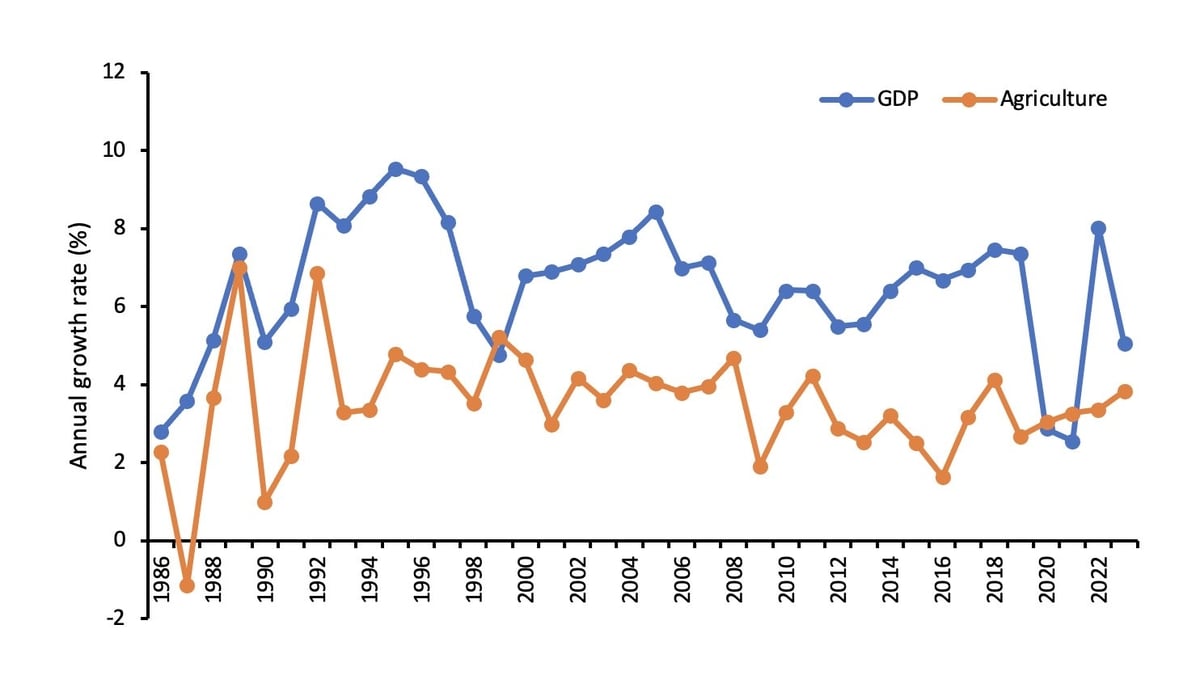

The “Doi Moi” reform created huge incentives for farmers and agri-businesses to continually raise food outputs. As a result, Vietnam’s agricultural sector grew at an average 3.5% per year between 1986-2023 (Chart 1). Between 1990 and 2023, farm-level outputs of coffee, rubber or cashew grew substantially, whereas poultry, pig or fishery production increased two to ten-fold.

Chart 1: GDP and Agriculture Growth Rates, %. Source: GSO.

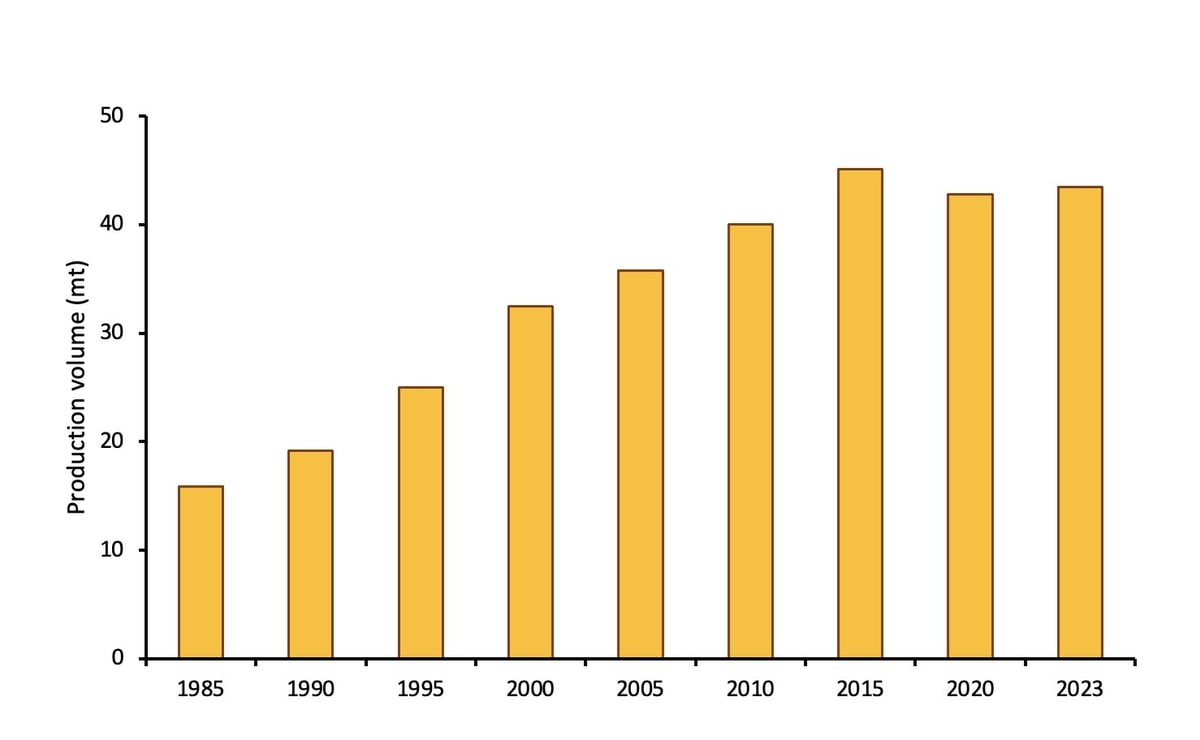

Vietnam turned from a net food importer to the world’s third largest rice exporter. In 2023, on just less than 4 million ha of land, Vietnam produced yearly more rice than all of Africa (Chart 2). In 2024, the country exported US$ 62.5 billion in agricultural, forestry or fisheries produce. Vietnam further aims to become one of the world’s top-10 agri-food processing hubs in 2030.

Though policy reform created strong incentives for the transformation of Vietnam’s agriculture sector, science and technology provided the necessary know-how. Presently, more than 90% of Vietnam’s farm premises are planted with improved varieties of rice, maize, cassava, sugarcane, coffee or rubber, many of which are drought-tolerant or resistant to debilitating pests and pathogens. Similarly, new breeds of pigs, chickens, shrimps, and catfish are widely adopted. Technical aspects of crop and livestock production also continuously improved. More than 90% of Vietnam’s rice crop is now mechanically harvested, high-tech greenhouses are increasingly set up for horticultural production, and livestock is increasingly produced in (automated) modern farms.

Chart 2: Rice production, Million tons of paddy. Source: GSO.

These improvements were mirrored in superior yield and quality of harvested produce. Vietnam’s yields of rice, coffee or rubber are now a respective 29%, 316% and 61% higher than the global average, whereas some of its rice varieties have twice been recognized as the world’s best. Fast-paced improvements in post-harvest processing over the past decades have further reduced agricultural losses while adding product value.

Over the past five decades, Vietnam has benefited from technical and/or financial support, both bilaterally and through international organizations such as FAO of the United Nations and institutions within the CGIAR (the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research). This has allowed the country to establish the necessary policy and techno-scientific capabilities to transform its agriculture sector. For example, in the period 1980-2008, three-quarters of Vietnamese rice varieties could be directly traced to the pedigree of the International Rice Research Institute IRRI-CGIAR.

Vietnam’s aquaculture sector has advanced with large strides, partly thanks to the know-how brought by different international partners. Regionally coordinated releases of beneficial insects tackled debilitating invasive pest problems in cassava or coconut, yielding social-environmental benefits across Vietnam’s countryside. Meanwhile, institutions such as the World Bank, ADB and IFAD have financed these developments, thereby encouraging FDI and generating rural employment.

Despite its notable achievements, Vietnam's agriculture is facing four prominent challenges.

Not all sub-sectors have benefited equally from the techno-scientific advances post-1986. As local maize, beans or cotton cropping and cattle raising are typified by low production efficiency, Vietnam’s agriculture in those subsectors is notably lagging behind.

Vietnam’s farmers' incomes remain low. With monthly per-capita incomes as low as US$170 (2023), the rural-urban income gap progressively widens. As a result, many farmers shift to non-farm activities, while youngsters tend to leave the countryside.

Vietnam’s agriculture has become overly reliant upon costly petroleum-derived inputs, including chemical pesticides and fertilizers, fuel, and antibiotics. Vietnam’s vegetable growers, for instance, overspend US$300-400 per cropping season and hectare on pesticides. Those input dependencies depress incomes, generate greenhouse gas emissions, jeopardize food safety and healthy diets, and harm biodiversity.

Unsustainable intensification practices further undermine the long-term sustainability of Vietnam’s agriculture. Extractive production methods aimed at short-term yield maximization can lead to a progressive degradation of farmland ecosystems, triggering erosion and soil fertility decline.

Agroecology is considered a means to revitalize its agriculture sector. Photo: VAN News.

To cope with the above challenges while pursuing the sustainable development goals, Vietnam opted to put its agriculture on a ‘green growth’ track and chose decisively for agroecology as general approach for food system transformation. In 2022, Vietnam’s Government launched a strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development for 2025-2030 with a vision toward 2050. Through this strategy, the country aims to use agroecology as a means to revitalize its agriculture sector, modernize its countryside and benefit societal wellbeing at large. A bold, comprehensive action plan on Food system transformation to 2030 aiming to connect better sustainable production and consumption has been devised to put this transformation in motion. This involves eight key aspects.

- Restructure agriculture based on comparative advantages and market demands;

- Ensure efficiency and sustainability by adjusting critical components of agri-food value chains, closing nutrient loops and alleviating input dependencies;

- Promote horizontal and vertical cooperation of actors along value chains and in the food systems;

- Develop rural off-farm activities;

- Modernize the countryside in conjunction with urbanization, protecting folk culture, food heritage and traditional landscapes;

- Pursue inclusive, equitable development;

- Promote community development e.g., by shifting the emphasis from yield gain to long-term revenue and societal wellbeing, including nutrition security.

- Intensify agricultural and food production in a responsible manner, protecting the environment, strengthening resilience against recurrent floods or droughts and supplying healthy diet access for domestic consumption, improving nutrition security and food safety.

Sound intensification of Vietnam’s agriculture is within reach. FAO-coordinated training programs during the 1980s-90s already reduced pesticide use by up to 92% in locally-grown cabbage, tea or rice crops, simultaneously enhancing farm profits, food safety and biodiversity. Given the major advances in biotechnology, genetics, digital tools and artificial intelligence (AI) since the late 1900s, one can surely place the bar even higher. To achieve those goals, market-oriented policy reform will continue while science, technology, and innovation can be harnessed to turn Vietnam into a 21st-century agricultural powerhouse. This while actively preserving the interconnected health of people, animals, and the environment, or One Health.

In a world grappling with food insecurity and environmental degradation, enhancing total factor productivity (TFP) - the efficiency with which inputs like labor, land, water, and fertilizers are converted into agricultural produce - offers a path forward. Agroecology, a science and practice rooted in ecological principles, is emerging as a transformative approach to sustain (or even raise) crop yields in the face of climatic upheaval while preserving biodiversity, soil health and environmental integrity. By integrating scientific and farmer knowledge, bridging social and natural sciences, and infusing place-based solutions with AI, genetics or digital tools, agroecology could redefine sustainable farming for the 21st century.

Agroecology, a science and practice, aims to increase productivity while preserving biodiversity, soil health and environmental integrity. Photo: VAN News.

Over the past four decades, Vietnam has successfully transformed its agriculture. Market-oriented reform, paired with sound policies and strong techno-scientific development, was a core determinant of this success. From 1986 onward, Vietnam’s agriculture became the motor of its impressive economic growth and social stability, generating stable food supplies, securing foreign valuta and lifting millions out of poverty. Yet, business as usual is no longer adequate or desirable. Whereas unsustainable farming methods lifted short-term yields, they can negatively affect farm profits, food safety, environmental integrity and resilience. Vietnam’s Government decision to put agriculture on a ‘greener’ growth trajectory can remediate these issues. It will ensure that intensification does not come at the expense of people, climate, or the planet. Intensifying Vietnamese agriculture according to new principles offers a powerful lever, while science, innovation and technological development can play a decisive role. This shouldered with FDI and Development Partners along with South-South/Triangular Cooperation (SSTC). Under experienced management and leadership, taking bold initiatives, a bright future undoubtedly lies ahead.

Cao Duc Phat, Dr of Agricultural Economics (Belarus), MPA (Harvard), Former Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development of Vietnam (2004-2016) and Vice Minister (1999-2003); Former Chair, Board of Trustees International Rice Research Institute, Philippines.

Dao The Anh, Dr of Agricultural and Rural Economics (France), Former Vice president of Vietnam Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VAAS), Member of French Academy of Agriculture, Member of CIRAD Scientific Committee (France).

Kris Wyckhuys, PhD, Entomologist / IPM Specialist, Honorary Associate Professor at University of Queensland, Guest Professor at Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences CAAS, former CGIAR research scientist in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Ad Spijkers, MA, Agricultural and Rural Development, Former FAO Representative in Asia and and Africa for thirty years and an advisor to the Director-General of the FAO in Africa and the Middle East. From 1985 to 1990 he worked in Vietnam.

----------

Literature

Food for All. Uma Lele, 2021, p 642, 649

Transforming Vietnamese agriculture: Gaining more for less. World Bank Group, 2016.

Vietnam’s food security in times of environmental uncertainty, population growth & technological advances looking back to plan ahead, Hanoi, 25 October 2017.

Investing in farmers—the impacts of farmer field schools in relation to integrated pest management. Van den Berg, H. and Jiggins, J., 2007. World development, 35(4), 663-686.

Land Law, 2013

General Statistical Office, 2021. General census of agriculture and rural development 2020.

General Statistical Office, 2006. General census of agriculture and rural development 2005.

Government decision No 07/2021/ND-CP, enacted 27 January 202, On multidimensional poverty standards for the period 2022-2025.

Nguyen Sinh Cuc, Nguyen An Tiem. Half of a century of agriculture and rural development in Vietnam (1945-1995). Publishing house Agriculture, 1996.

Premier Minister Decision 150/QD- TTg, 28 January 2022. Approval of strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development in the period 2021- 2030, vision toward 2050.

Priority and removing difficulties in providing credit to agricultural and rural sectors. Banking Review. March 2023.

Resolution No 26 NQ/TW, 5 August 2008, of the Xth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside

Resolution No 19 NQ/TW, 16 June 2022, of the XIIIth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside by 2030, with the perspective to 2045

The World Bank, 2022. Vietnam climate and development report, 29 May 2025

(VAN) Despite pilot programs and support policies, agricultural insurance continues to generate less than 0.1% of the insurance market's total revenue.

(VAN) To comply with the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), Vietnam is accelerating the development of a national data system. This will guarantee that coffee, rubber, and wood exports continue without interruption upon the regulation's implementation.

(VAN) Organizations and individuals wishing to participate in forest carbon credit trading will follow the new regulations on forest carbon sequestration services.

(VAN) Reducing emissions from agricultural and food production is a potential solution for Vietnam to implement its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) 3.0.

(VAN) The national action plan for food system transformation needs to align with the decentralization requirements under Vietnam's upcoming two-tier government model.

(VAN) The Food and Agriculture Organization’s Strategic Framework and its Science and Innovation Strategy make a simple case: solving systemic problems requires systemic solutions.