June 14, 2025 | 10:08 GMT +7

June 14, 2025 | 10:08 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 14, 2025 | 10:08 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

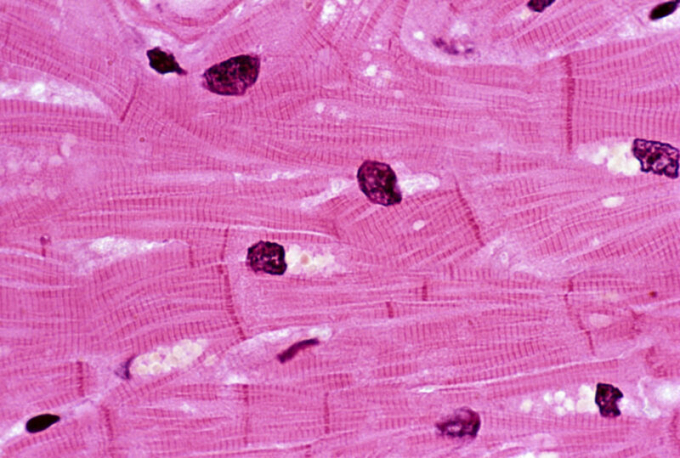

Much of the heart is composed of muscle cells like the ones shown here.

Earlier this year, news broke of the first experimental xenotransplantation: A human patient with heart disease received a heart from a pig that had been genetically engineered to avoid rejection. While initially successful, the experiment ended two months later when the transplant failed, leading to the death of the patient. At the time, the team didn't disclose any details regarding what went wrong. But this week saw the publication of a research paper that goes through everything that happened to prepare for the transplant and the weeks following.

Critically, this includes the eventual failure of the transplant, which was triggered by the death of many of the muscle cells in the transplanted heart. But the reason for that death isn't clear, and the typical signs of rejection by the immune system weren't present. So, we're going to have to wait a while to understand what went wrong.

A solid start

Overall, the paper paints a picture of organ recipient David Bennett as a patient who was on the verge of death when the transplant took place. He was an obvious candidate for a heart transplant and was only kept alive through the use of a device that helped oxygenate his blood outside his body. But the patient had what the researchers refer to as "poor adherence to treatment," which led four different transplant programs to deny him a human heart transplant. At that point, he and his family agreed to participate in the experimental xenotransplant program.

The pig that served as the heart donor came from a population that has been extensively genetically engineered to limit the possibility of rejection by the human immune system. The line was also free of a specific virus that inserts itself into the pig genome (porcine endogenous retrovirus C, or PERV-C) and was raised in conditions that should limit pathogen exposure. The animal was also screened for viruses prior to the transplant, and the patient was screened for pig pathogens afterward.

After the transplant, the patient's new heart performed well, displaying a normal rhythm between 70 and 90 beats per minute. Most significantly, over half the blood that filled the left ventricle of the transplanted heart was sent out into the circulatory system with each contraction; that was up from only 10 percent in the diseased heart it had replaced.

At about two weeks after the transplant, Bennett started experiencing abdominal pain and weight loss that ultimately resulted in him losing more than 20 kg (40 lbs). He was put on a feeding tube, and an exploratory laparoscopy showed potential signs of an infection that was resolving, but no action was deemed needed. A short while later, screening turned up a possible infection with the pig version of cytomegalovirus; the human version of this virus causes issues like pneumonia and mononucleosis. This was handled with antiviral treatments.

While the weight loss was an obvious concern, at five weeks after the transplant, there were no indications of rejection, and the heart was still functioning.

A turn for the worse

Things started to go bad about seven weeks post-transplant when Bennett's blood pressure began to drop, and he started having trouble staying awake. Fluid started building on his lungs, and he had to be intubated. Imaging showed that his heart was still clearing out most of the volume of the ventricles with each beat, but the total volume had shrunk as the walls of the ventricle thickened. Eventually, external oxygenation had to be restarted.

Pig DNA began to show up in the bloodstream, indicating tissue damage; some anti-pig-cell antibodies were also detected, suggesting a degree of rejection. But a biopsy failed to find any signs of it in the heart tissue; instead, there were signs that capillaries in the heart were leaking, creating swelling and allowing blood cells into the heart tissue.

A week later, a second biopsy indicated that about 40 percent of the heart muscle cells in the transplant were dead or dying, even though there were still no indications of rejection in the tissue. That level of damage brought an end to things: "We concluded that an irreversible injury to the xenograft was present and, with the patient’s family at the bedside, compassionately withdrew life support on day 60 after transplantation."

So, what have we learned?

After death, the team performed an autopsy on the transplanted heart. They found that it had nearly doubled in weight, largely because of fluid (and some red blood cells) leaking out of blood vessels in the absence of clotting. There was significant death of heart muscle cells, but that was scattered across the heart, rather than being a general phenomenon. Critically, most of the indications of a strong immune rejection were missing.

The presence of an apparent pig cytomegalovirus was worrying, but the researchers indicate there's some question about whether the tests that picked it up might have been recognizing a closely related human virus—one that's often associated with organ transplant problems.

So, for now, it's not clear what happened with this transplant or what the significance of the apparent viral infection is. Obviously, the team has lots of material to work with to try to figure out what went on, and there's a long, long list of potential experiments to do with it. And there are also additional xenotransplant trials in the works, so it may not be long before we have a better sense of whether this was something specific to this transplant or a general risk of xenotransplantation.

New England Journal of Medicine

(VAN) Extensive licensing requirements raise concerns about intellectual property theft.

(VAN) As of Friday, a salmonella outbreak linked to a California egg producer had sickened at least 79 people. Of the infected people, 21 hospitalizations were reported, U.S. health officials said.

(VAN) With the war ongoing, many Ukrainian farmers and rural farming families face limited access to their land due to mines and lack the financial resources to purchase needed agricultural inputs.

(VAN) Vikas Rambal has quietly built a $5 billion business empire in manufacturing, property and solar, and catapulted onto the Rich List.

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.