June 14, 2025 | 07:41 GMT +7

June 14, 2025 | 07:41 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 14, 2025 | 07:41 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

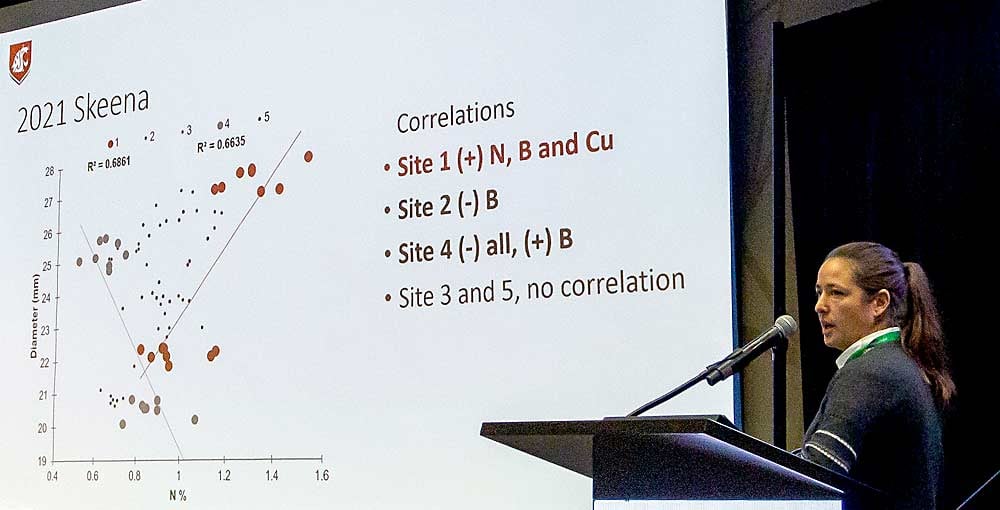

Bernardita Sallato of Washington State University tells growers that, in her research, cherry fruit quality metrics showed little correlation to their nutrient content, during a presentation at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December in Yakima.

Bernardita Sallato of Washington State University suspects many growers overfertilize their fruit trees.

With margins so tight in the industry, the extension specialist with a soils background is urging orchardists to reduce their applications of nitrogen, calcium and other macronutrients to farm with more precision and save a little money.

For years, nutrients were a marginal expense, compared to the costs of labor, and excess rarely causes harm. So, growers typically shrugged and erred on the side of abundance.

Perhaps it’s time to sharpen the pencil, Sallato said. She has been receiving calls from growers asking her how to keep trees alive with as few nutrients as possible.

“Maybe this is the year that’s an opportunity for them to evaluate,” she said.

In grower meetings this winter, Sallato shared a chart of the share of cherry and apple growers who fertilize too little, too much or just right — that is, within recommended levels — based on several of her research projects at more than 200 sites.

The number of excess instances was surprising, she said.

At the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December, she shared data showing cherry fruit quality metrics — size and firmness — rarely tracked with nutrient levels across three years of fruit, leaf and soil samples from 11 orchards with multiple varieties.

Some soft cherries correlated to low nitrogen, but only in extreme cases. Her data showed no difference in calcium concentrations between firm and soft fruit. In fact, the site with the highest quality received the least calcium.

As for apples, Sallato and other researchers have long argued crop load is more important than calcium in the fight against bitter pit, a Honeycrisp disorder caused by a nutrient imbalance in the fruit. She questions whether foliar calcium sprays are worth growers’ money.

She recommends determining nutrient demand by projecting yield and deducting the amount already available as measured by soil and tissue analyses, usually done once per year. Consider water testing, too, because nutrients in irrigation water might affect the equation, she said.

Growers sometimes respond with enthusiasm to her austerity message but don’t always change their practices, she said. Other than saving money, they don’t have much incentive; excesses don’t usually hurt.

The salts of any foliar nutrient spray can burn leaves during hot weather. However, calcium is rarely toxic because trees crystalize excess, just to get rid of it. Potassium poses little threat by itself, though it can impede calcium uptake. With nitrogen, only a drastic oversupply would be toxic, but even a little excess can throw crop load out of balance.

After visiting Gilbert Orchards of Yakima in 2023, Sallato persuaded general manager Rob McGraw to reduce calcium.

The farm has always tested soil and tissue, but since following Sallato’s instructions, his crews have adjusted timing and pushed their first fertigation applications to a narrow window later in the spring, after roots start to grow. They now stop roughly 40 days after bloom. Calcium does not move quickly through trees.

After that, they still apply foliar sprays but only half as much as they used to and only as part of a tank mix, usually with fungicides.

They haven’t noticed any drop in quality, and they’re saving money on material and labor.

“I think we were spending way too much money on injecting calcium way beyond the time that was still effective,” McGraw said.

Garrett Henry of Douglas Fruit Co. near Pasco also tests soil and tissue, and he also has adjusted nutrition in the wake of Sallato’s advice.

He used to apply nitrogen in the fall but has switched to spring to hit the period of root growth. He targets low nitrogen rates, about 30 pounds, for Honeycrisps and Fujis, to avoid bitter pit and alternate bearing.

As for potassium, he once aimed for 250–300 parts per million but now tolerates as low as 175 for varieties sensitive to bitter pit.

When it comes to foliar calcium, he sticks to tank mixes but won’t stop completely. The sprays may not prevent bitter pit, but they might nudge quality a little higher. And for his highest-value varieties, a little bit is worth it, he said.

“I think most guys will tell you, ‘I’m not sure it works, but I’m not going to take it out of my program,’” Henry said.

Dain Craver, an organic grower near Royal City, appreciates Sallato’s science but is skeptical about cutting calcium.

He’s happy with his packouts. He’s willing to adjust practices, but 45 years of experience tell him calcium is worth the cost with his organic margins, he said.

“I just don’t try to reinvent the wheel,” he said.

He carefully prunes and thins to manage crop load, but he also applies about 1,000 pounds per acre of gypsum — a form of calcium — to the soils in his Honeycrisp blocks. He also puts liquid calcium on the ground.

He applies four or five foliar sprays of calcium starting at pink bloom. When fruitlets reach about 30 millimeters, he switches to two forms of calcium chloride, in effect doubling the rates, but only with overhead cooling. He usually tank-mixes with fungicides and insecticides but sometimes makes calcium-specific sprays.

In cherries, he includes calcium chloride in tank mixes to prevent rain cracking. It helps prevent the skin from absorbing water but sometimes browns the stems.

Mike Omeg, a cherry grower in The Dalles, Oregon, takes data-driven nutrition even further by comparing old and new growth.

Every other week throughout the season, he samples base leaves and new leaves from blocks with historical data. A laboratory in the Netherlands processes the samples, allowing him to spot changes and trends and to adjust his applications accordingly.

He considers his boost in efficiency and fruit quality worth the extra cost.

“I understand when people say, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s expensive,’” he said, “but nutrients are expensive, too.”

As for calcium, he considers it critical to fruit size, quality and resilience to heat, rain and wind.

He blends gypsum with nitrogen soil applications in the spring, fertigates with calcium occasionally and applies foliar calcium as part of a nutrient blend he adjusts as needed. He sticks with tank mixes.

He agrees the industry could use more precision with nutrients.

“That’s an area where there is room for improvement,” Omeg said. •

goodfruit

(VAN) In Tien Giang, a high-tech shrimp farm has developed a distinctive energy-saving farming model that has yielded promising results.

![Turning wind and rain into action: [3] 300.000 farmers benefit from agro-climatic bulletins](https://t.ex-cdn.com/nongnghiepmoitruong.vn/608w/files/news/2025/06/12/e5a48259d6a262fc3bb3-nongnghiep-125122.jpg)

(VAN) The agro-climatic bulletin has become a valuable tool for farmers in the Mekong Delta. After more than five years of implementation, the initiative is gradually being expanded nationwide.

![Turning wind and rain into action: [2] Providing forecasts to the people](https://t.ex-cdn.com/nongnghiepmoitruong.vn/608w/files/news/2025/06/12/e5a48259d6a262fc3bb3-nongnghiep-103927.jpg)

(VAN) In addition to improving the quality of hydrometeorological forecasts, putting forecast bulletins into practical use is crucial for production and disaster prevention.

(VAN) Blue carbon is receiving attention for its rapid absorption capacity and vast potential. It represents a promising nature-based solution to respond to climate change.

/2025/06/11/3507-1-161904_583.jpg)

(VAN) Seagrass beds and coral reefs serve as 'cradles' that nurture life in the ocean depths, creating rich aquatic resources in Vietnamese waters.

![Turning wind and rain into action: [1] Forecasting for farmers](https://t.ex-cdn.com/nongnghiepmoitruong.vn/608w/files/news/2025/06/11/e5a48259d6a262fc3bb3-nongnghiep-111919.jpg)

(VAN) Weather is no longer just a matter of fate. Forecasts have now become an essential companion for farmers in every crop season.

/2025/06/10/2501-3-082025_983.jpg)

(VAN) Mr. Le Hoang Minh, Head of Vinamilk's Net Zero project, recently shared insights on the integration of production, energy, and technology in Vinamilk’s green transition journey.