June 18, 2025 | 11:42 GMT +7

June 18, 2025 | 11:42 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 18, 2025 | 11:42 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

High wheat prices don’t mean Colorado farmers are getting rich. Most are worried about just getting a crop. The price of a bushel of wheat has nearly doubled since Russia invaded Ukraine. That’s because the two countries make up almost a third of the global wheat trade.

While the top dollar being offered on the open market might make the wheat crop just poking up from the ground on thousands of acres on Colorado’s Eastern Plains seem like a pot of potential gold, there’s virtually no effect on the fortunes of Colorado wheat farmers.

Some experts are warning of potential food shortages as a result of the war in Ukraine, but most Colorado growers aren’t in a position to step up production. They’ll be lucky to harvest as much as they did last year.

Wheat prices over the last year

A bushel of wheat cost around seven dollars for the past year, but after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it peaked at nearly $13.

Source: www.macrotrends.net

Persistent drought has put much of this year’s crop at risk. The predominant variety grown in Colorado is winter wheat, planted in fall to take advantage of winter moisture that didn’t come. Insect pests are out of control while production costs have gone way up. Most farmers already sold all their grain from last season, so they can’t benefit from the high prices caused by the war in Ukraine.

“We’re not getting rich at all,” said Baca County farmer Brian Brooks, who is president of the Colorado Association of Wheat Growers (CAWG). “Ten dollar wheat, everybody’s excited. But we have to pay for the inputs.”

Colorado Wheat, a research organization that encompasses CAWG, assesses the state of the crop every week. The most recent report, on March 27, was grim. About half of the wheat on the 2.1 million acres planted last fall is in fair condition, a quarter of it is poor, and 14% is very poor. Only 11% is good and 0% is excellent. The lack of a solid crop threatens the Colorado economy because wheat brings in more than $250 million annually.

What’s happening in Ukraine and Russia may affect grain markets in the long term, but there are four other things Brad Erker, executive director of Colorado Wheat, is far more worried about: drought, the cost of doing business, insects and a lack of leftover grain from last year.

Let’s break down Erker’s list of the five things most impacting this year’s wheat crop.

Drought

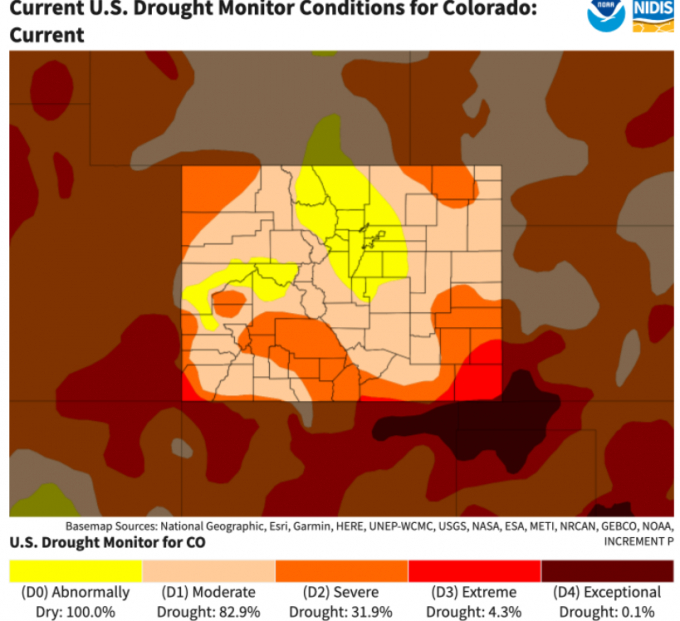

Source: USDA

The yearly wheat harvest doesn’t happen until the summer, but Brooks already knows he won’t produce a dryland crop this year from his farm in southeastern Colorado. He said some of his wheat sprouted and died while some of it never came up.

“We’re hopeful and we pray for rain every day,” Brooks said. “But as far as our wheat crop, we’re already finished, on the dryland aspect. We’re just hoping for spring rain to plant our spring crops.”

Brooks is one of a few Colorado farmers who was able to irrigate a portion of his wheat crop. He will plant irrigated corn around the first week of May. He’s had some success with his irrigated crop this year, but irrigation is rare among Colorado wheat farmers. Most have no choice but to wait for rain, Erker said.

All of Colorado is abnormally dry this year. Moderate drought is reported in 82.9% of the state and more than a third of Colorado reaches levels of severe drought. In Baca County, where Brooks farms, 97.08% of the land is experiencing the type of drought that puts cash crops, like wheat, sorghum and corn, at risk.

Colorado hasn’t seen conditions this bad in a decade, Erker said.

Brooks said the last big moisture event in his corner of the state happened in early August. Precipitation this year has been sporadic and farming conditions have been made worse by wind that caused erosion.

Much of the wheat crop didn’t get off to a good start after it was planted in the fall, Erker said. Conditions worsened with a dry winter, leading to an uneven emergence of the crop.

The situation varies across the state’s 2.1 million acres planted with wheat. Brooks said farmers he knows in northern Colorado aren’t experiencing the same exceptional drought conditions that he is. Still, Erker said, many farmers are concerned that without moisture soon, they won’t have much of a wheat crop this year.

“We’re not very optimistic about the weather turning around and starting to rain like it did last spring,” Erker said.

Professor Stephen Koontz of Colorado State University’s Agricultural and Resource Economics Department shared the same sentiment.

“The wheat crop really needs a couple of substantial rains in May,” Koontz said. “And if you can find me somebody who can forecast those, I’ll call them a liar for you.”

The drought also reduces potential yield because wheat is unable to effectively tiller, or branch from the main shoot to create multiple seed heads. Tillering, which usually occurs shortly before or after winter dormancy, increases the output of wheat.

The less rain in the forecast, the higher the chances become of farmers abandoning their fields or giving up on their crop to collect insurance. Brooks said he doesn’t really make any money off of his insurance policy, but it helps him get to the next year. If there isn’t enough rain to plant his spring crops without risking erosion, the insurance will help him get to the fall for another round of wheat.

The crop insurance system is more substantial now than in recent years, Koontz said. He said the program gives important protection, especially to dryland farmers.

“My easiest recommendation for producers going forward is to do things like make sure you have crop insurance bought,” Koontz said.

Insect pests

The wheat stem sawfly is a grass-feeding insect that has infested winter wheat in Colorado since 2010. The pest mainly damages wheat in the northeastern part of the state, although it has attacked crops as far south as Brooks’ Baca County.

There’s no insecticide that can kill or control them, and the parasitic wasps that serve as predators haven’t made an impact.

“It’s basically an uncontrollable insect pest that’s wreaking havoc on the northeast Colorado crop,” Erker said.

The sawflies eat through the stem of the wheat about a week or two before harvest, causing the plant to weaken and fall flat on the ground. The fallen wheat makes it harder to harvest, and reduces the quality and quantity of the yield.

Wheat stem sawflies were reported on 60% of the acres that grow wheat in Colorado last year, according to Colorado Wheat director of communications and policy Madison Andersen. That’s more than a million acres infested by the pest.

The most frustrating part? Winter wheat growers have no way to know whether their fields are infested until just before the harvest.

“Two weeks out from harvest, your crop’s on the ground,” Andersen said. “It’s crazy.”

Colorado Wheat is funding research through Colorado State University to find solutions to the wheat stem sawfly infestation.

High Input Prices

Farmers are having to pay more to protect their crops. The price of fertilizer has more than doubled since last year. The common herbicide glyphosate, known as Roundup, that controls weeds to try to save moisture is up 200% to 300%, Erker said.

Brooks paid $420 for a ton of the nitrogen fertilizer anhydrous ammonia last spring. Now he gets it for $1,350.

While the cost of fertilizer, weed control chemicals and fuel has doubled or tripled, the availability and supply of these products can be an issue, Brooks said.

“Just the inputs are astronomical,” Brooks said. “I try not to be a doom-and-gloom guy, but it’s hard to talk about this and not be kind of down.”

Most fertilizer applied to this year’s crop already went on the wheat in the fall, when prices were lower. Koontz said topdressing applications will be more limited this spring due to the high prices, but noted that that process occurs more often in the southeastern U.S. where wheat is more aggressively fertilized and gets more rain.

Fertilizer prices won’t come down for at least two years, but possibly upward of three or four, Koontz said. That means farmers with low yields due to drought or insect pests might struggle for years to bounce back.

“The input costs are going to be atrocious,” Koontz said. “The issue for wheat producers will be: they’ve got a dry year this year, they’ve got reduced yields to sell into a very good market, and then they’ve got a very painful situation for the coming fall of being able to secure fertilizer.”

Even if Brooks’ irrigated wheat crop does well this year, he said the input costs will take a large chunk of the profit. And as input prices increase, the profit margins for farmers will continue to narrow.

Brooks said he is concerned about that pressure because of the war in Ukraine. He said he thinks a resolution to the conflict could stabilize global wheat markets, but might not bring input costs back to normal. If wheat prices fall while input prices remain high, farmers could be set up for loss.

“That’s my biggest fear,” Brooks said.

Lack of grain

Another reason many farmers can’t take advantage of the high prices caused by the war is simply the timing. Nobody’s wheat is ready for market at this point in the year.

Winter wheat in Colorado is planted around September. It grows through the fall, goes dormant in the winter, emerges from dormancy to grow through the spring and is harvested around July.

“You really can’t decide at any other time point in the year that you’re going to try to put in more wheat,” Erker said. “It’s not like a factory where you can decide to crank out more widgets next month. We operate on a yearly cycle, not a monthly or weekly cycle.”

Some years, farmers store extra grain because they anticipate higher prices. But a lot of selling occurred last July and August because prices were rising and looked better than the previous year. The prices received for winter wheat in Colorado jumped to $6.03 per bushel in July 2021 from $4.23 in July 2020.

Colorado produced 75 million bushels of wheat last year, but only 4.5 million bushels are still stored on farms, Erker said. He said that’s the second lowest on-farm wheat stocks in Colorado since 2000.

“It’s sort of discouraging for the farmers,” Erker said. “You finally have a chance to have prices up after being low for many years, and you’ve sold last year’s crop already, and you don’t have very good prospects for this year’s crop.”

Some growers with leftover wheat have been able to capitalize on the recent uptick in wheat prices. Erker says that didn’t happen for the majority of anyone’s crop.

For most farmers, it happened to none of their crop. Brooks had sold all of his wheat from last year before the prices jumped.

“The last I sold out was for $8.50, which I mean, last year we had lower input costs, so I made money with that,” Brooks said. “But almost all the farmers down here have sold out.”

High wheat prices

So, a lot of Colorado farmers don’t have very much wheat to sell right now. But couldn’t they still take advantage of the high wheat futures?

Technically yes, but it’s not that simple.

Farmers could sell their wheat at these high prices by forward contracting, or agreeing on a price now for wheat to be sold in a few months. But because of the drought, many farmers are hesitant to contract a substantial portion of their crop.

“If you don’t know that you’re going to be able to produce the wheat, you don’t want to contract it,” Erker said. “If you don’t produce it, you could have to buy very expensive wheat to deliver on that contract.”

Most farmers won’t have a chance to capitalize on wheat prices until after the harvest this summer. And that’s if they have a crop.

“If we had a dryland (crop), it would be a different ballgame and we could do well at these prices,” Brooks said. “But we’re just gonna have to watch ’em go by.”

Russia and Ukraine were the first and fifth largest exporters of wheat in 2020, respectively. Most of Ukraine’s wheat is exported in late summer, but some of their other imports are currently down because of port closures. The Port of Odessa, Ukraine’s largest, has been closed since the Russian invasion in February. Russia has implemented export taxes and an export quota, according to the same USDA report, meaning less of Russia’s wheat is on the global market and it costs more to get what’s available.

If access to Russian and Ukrainian wheat is still down this summer after the harvest, the wheat produced by other countries to make staples like bread and pasta becomes more valuable.

“In the longer term, those factors could have a huge impact all the way over here to farmers in Colorado,” Erker said.

Koontz thinks these high prices are here to stay, at least for a little while. Given the pent-up demand and low supplies due to the pandemic, the world economy is strong with a favorable market for producers. He estimates that farmers with more than 60% of their typical yields will make a profit off of these prices.

“I think this will be a benchmark year,” Koontz said. “This is one that will likely play out to have incredibly high commodity prices. I see it really persisting through this year, and quite possibly next and the year after that.”

Many farmers like Brooks won’t benefit from the high commodity prices this year because of low yields. But he said he’s still hopeful for the upcoming season.

It goes back to something his grandad always said: “this is good next year country.”

“You know what, this is good country,” Brooks said. “God will send us rain, and just know next year it may look like a beautiful garden out here. You never know.”

(Coloradosun)

(VAN) Extensive licensing requirements raise concerns about intellectual property theft.

(VAN) As of Friday, a salmonella outbreak linked to a California egg producer had sickened at least 79 people. Of the infected people, 21 hospitalizations were reported, U.S. health officials said.

(VAN) With the war ongoing, many Ukrainian farmers and rural farming families face limited access to their land due to mines and lack the financial resources to purchase needed agricultural inputs.

(VAN) Vikas Rambal has quietly built a $5 billion business empire in manufacturing, property and solar, and catapulted onto the Rich List.

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.