June 3, 2025 | 06:16 GMT +7

June 3, 2025 | 06:16 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 3, 2025 | 06:16 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

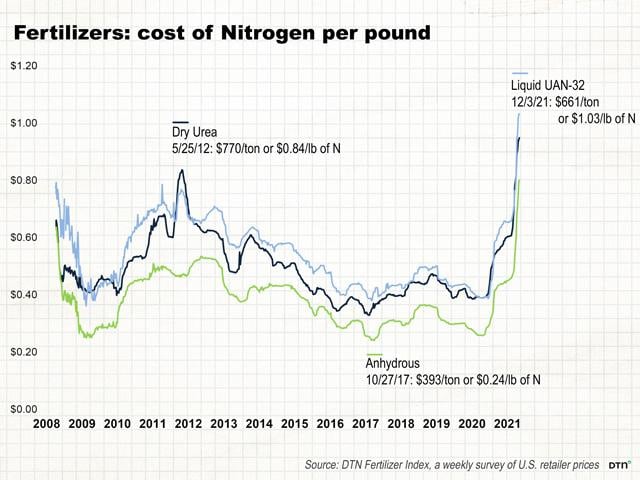

Prices for dry urea fertilizer are 143% above year-ago levels, but only 13% above the previous all-time high from 2012. Source: DTN

"Peruvian guano has become so desirable an article to the agricultural interest of the United States that it is the duty of the Government to employ all the means properly in its power for the purpose of causing that article to be imported into the country at a reasonable price. Nothing will be omitted on my part to accomplishing this desirable end." -- President Millard Fillmore in his Dec. 2, 1850, State of the Union Address, promising to bring down the market price of bird poop.

In fact, President Fillmore devoted 100 words of his 1850 State of the Union address to the topic of bird droppings, over 1% of the entire speech, alongside talk of international canals and railroads that would advance global commerce. The topic of manure -- any type of manure -- was a very big deal in those days, and these days, too. Farmers today can sympathize with that high-consequences attention to the topic of fertilizer and devote at least that much scrutiny to record-high prices today.

Back in 1850, there was no such thing as synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, and if anyone ever wanted to get better than 20 bushels per acre of corn, farmers had to use whatever natural fertilizer they could find -- farm animal manure, sure, but also kitchen waste, sawdust, dead animals, sludge from wetlands; you name it. In the "Guano Age," a powerful global industry had sprung up to mine giant mountains of desirable bird poop off the coasts of Peruvian islands (and elsewhere), yet there still wasn't enough supply to meet demand. Seabird guano reportedly hit a high of $76 per pound in 1850, or a quarter of the price of gold.

That's so expensive, it's beyond comparing to today's common agricultural fertilizers. Assume you can get 70 pounds of nitrogen per ton of seabird guano (3.5% nitrogen), similar to some poultry litter available today, and it shows anyone actually buying guano at $76 per pound was paying over $2,000 per pound of nitrogen. There's no way this could have been a widespread market price paid by the average American farmer, but nevertheless, today's anhydrous ammonia at $1,314 per ton (or $0.80 per pound of nitrogen) doesn't seem so bad!

To be sure, the prices for nitrogen-based fertilizers are as high as they've ever been. The DTN Fertilizer Index, a weekly survey of over 300 retailer prices, showed dry urea averaging $873 per ton in the first week of December 2021. With 920 pounds of nitrogen provided to a crop from each ton of urea, that's $0.95 per pound of nitrogen. With liquid UAN-32 fertilizer priced at $661 per ton and 640 pounds of nitrogen available from each ton, that's $1.03 per pound of nitrogen -- now the highest price for nitrogen since the Guano Age.

In year-over-year terms, dry urea prices are 143% higher than in early December 2020, but looking at a longer timescale, today's urea prices are only 13% above their peak from the 2012 planting season. You can watch fertilizer prices rise week by week, like anhydrous, which has been rising by an average of 6% per week since October, in the DTN Retail Fertilizer Trends series by DTN Staff Reporter Russ Quinn:

Nevertheless, it's no wonder that many grain producers are looking for alternatives to high-priced synthetic fertilizers. Although I don't have access to a nice, long-term data series of manure prices from cattle feed yards, for instance, let's assume the value of cattle manure today is at about $70 per ton. If it makes 5 pounds of nitrogen available per ton of manure, that's equivalent to paying $0.18 per pound of nitrogen (and getting all the other minerals and benefits of organic matter for free). This would be by far the cheapest source of nitrogen, if it's available to you and logistically feasible to apply. But just like the guano of the 1850s, there's only so much to go around.

Interestingly, phosphate-based fertilizers remain cheaper now than they were during the commodity boom of 2008 (an N-P-K mix of 10-34-0 in November of 2008 was priced at $1,250 per ton but is now only $756). Altogether then, fertilizer prices shouldn't seem quite as panic-inducing, as a one-year anhydrous chart (up 208% year over year) might strike us at first glance. It's not some new, overwhelming, unmeetable demand for the stuff that's causing the rally -- rather, it's the global shortage of nitrogen itself that is the driving force behind rising fertilizer prices.

Ever since German chemist Fritz Haber and metallurgist Carl Bosch figured out the famed Haber-Bosch process (1909) to artificially fix atmospheric nitrogen into the usable nitrogen of ammonia under high temperatures and pressures, the world's supply of nitrogen has more or less depended on the world's supply of natural gas. In commercial fertilizer production, natural gas is used not only as the source for raw hydrogen in the chemical reaction, but also to provide the necessary heat. Today, U.S. natural gas prices have come down from their September peak, but in Europe there is still massive uncertainty about receiving natural gas supplies from Russia amid current geopolitical tensions and some fertilizer plants remain shut down until natural gas prices moderate. For at least the next several months, the global outlook for fertilizer availability will remain as tense as the Russia-Ukraine border.

Just as a new technology (synthetic fertilizer production through the Haber-Bosch process) ultimately relieved the shortage of guano in the 20th century and made a golden age of agriculture and human prosperity possible, is there perhaps a new technology on the horizon that will alter our dependence on natural gas to feed the world? Researchers at Australia's Monash University have recently announced a breakthrough new method to produce "green" ammonia with a different catalyst than the Haber-Bosch process, at room temperature, at efficiency rates that may someday be commercially viable.

In the meantime, until there's abundant commercially produced green ammonia, if you're unable to source the usual synthetic fertilizers necessary for spring planting at your local retailers, perhaps you'd like to consider something more old school, like this Mexican bat guano you can buy on the internet for $7.50 for a 1.25-lb bucket from a natural gardening outlet.

That's probably equivalent to $6.67 per pound of nitrogen, so maybe it's better to stick with anhydrous. Anyway, even the bat guano is out of stock these days!

(DTNpf)

(VAN) Vikas Rambal has quietly built a $5 billion business empire in manufacturing, property and solar, and catapulted onto the Rich List.

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.