May 25, 2025 | 22:35 GMT +7

May 25, 2025 | 22:35 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 25, 2025 | 22:35 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

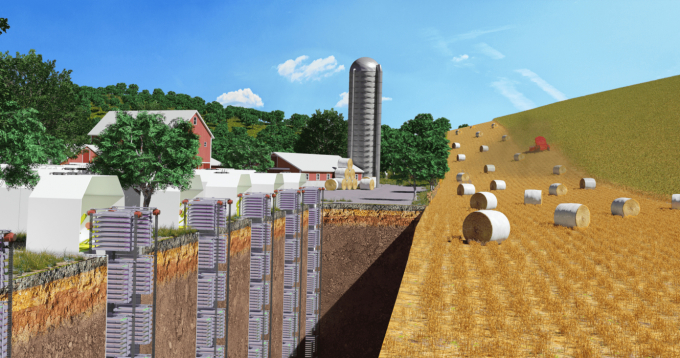

Photo: GreenForges

But Philippe Labrie is looking down. Labrie is the CEO and founder of the pre-seed startup GreenForges, an underground farming company founded in 2019 looking to take vertical farming technology underneath buildings. Earlier in his career, Labrie thought he, too, would be looking to the sky for farming potential with rooftop greenhouses. But he found that the sky does, in fact, have a limit.

“I stumbled upon a paper that was analyzing how much food production capacity can we do in cities using rooftop greenhouses,” he said. “It’s a relatively low number; we’re talking 2 to 5% range for the cities of 2050. No one was asking the question, ‘Can we grow underground?’”

Agriculture has always been a business fueled and restricted by space. When agriculture first emerged around 12,000 years ago, farmers had to clear forests for cropland. That destructive process has continued to this very day. In order for farmers to grow more food and make more money, they need more land. Traditional vertical farming tried to solve this land conversion issue by moving farms to urban environments and stacking the crops on top of each other. But the warehouses still have to sit somewhere. GreenForges is trying to take advantage of space that would otherwise go unused, under our feet.

After two years of research and development, the company is planning its first pilot underground farm system north of Montreal in spring 2022 with Zone Agtech, an incubator for agricultural technologies. The company’s farming system will use existing controlled indoor agriculture technology, including controlled LED lighting, hydroponic growing (growing without soil) and climate controls for humidity and temperature but with a novel approach.

Instead of taking over large warehouses, GreenForges will drill 40-inch-diameter holes into the ground underneath new buildings and lower the equipment into the hole. Maintenance and harvesting will be done by mechanically pulling the crops up to the surface where a human can fix or pick. The pilot program will place the farms 15 meters deep, but GreenForges has plans and models for farms up to 30 meters deep.

According to Labrie, moving the vertical farms from above ground to below comes with a host of other benefits, some directly solving the largest obstacle controlled environment agriculture farming faces — energy costs.

“For surface vertical farms, one of their biggest energy loads is constantly having to work that HVAC system because the exterior temperature is changing — hot, cold, wet, dry. They have to work it really hard just to keep the environment [inside] stable,” Labrie said.

Energy costs have made vertical farming more costly in terms of both emissions and dollars in some locations when compared to traditional farming. And it’s one of the main reasons many vertical farms stick to leafy greens; it’s just too energy-intensive to make growing anything else profitable. But going underground could immediately eliminate the challenge of maintaining a stable environment inside, while a changing one exists outside.

“The moment you go underground, now you become season-agnostic,” said Jamil Madanat, engineering manager at GreenForges. “This is where the holy grail of energy savings is going to take place.”

Madanat explained that anywhere in the world, no matter the time of year or environment, temperatures stabilize underground. In Malaysia, it stabilizes at 10 meters deep to 20 degrees Celsius. In Canada, at 5 meters deep, the temperature stabilizes to 10 degrees Celsius no matter the temperature above ground.

“When it comes to electricity or energy supply, the more steady it is, the better your economics work,” Madanat said. “When you have to consume a high amount of energy at once, and then drop it all at once, that’s not what the grid likes. The grid likes steady supply.”

Having a steady demand for energy because the temperature outside the underground farm is steady creates the potential for massive energy savings and sustainability. GreenForges is also able to do this with lighting by giving half the crops daylight while the other half gets night and alternating them so the energy needed for lighting is always the same.

Additionally, GreenForges is only looking at regions that get most of their energy from renewable electricity, like solar or hydropower, to avoid adding emissions to the environment through burning fossil fuels.

“It just doesn’t make sense to grow food indoors by burning stuff,” Labrie said.

GreenForges predicts that its underground system will increase energy efficiency by 30-40% compared to traditional vertical farms. Currently, the company is sticking with traditional indoor crops like leafy greens, herbs and berries. The company plans to produce about 2,400 heads of lettuce each month for a 100-foot farm, about 14,000 pounds a year. But Labrie hopes that with GreenForges’ increased efficiency, it will be able to graduate to other crops — even something as elusive and dramatic as wheat — in the future.

But of course, growing underground doesn’t come without obstacles. According to Madanat, creating growing equipment to fit in a tunnel about the size of two truck tires poses a design challenge. The company has had to create its own hardware solutions to fit and be able to extract the system in such a small space. Humidity is another enemy underground the company is battling.

Unlike vertical farm leaders, Plenty and Aerofarms, GreenForges doesn’t want to become a grocery produce brand. Instead, Labrie is focusing on appealing to the builders of new high-rise hotels or apartment buildings, creating an extra perk of fresh produce for guests or tenants and a new revenue stream.

“We see a lot of potential with integration in buildings. We have interest from hotel companies and real estate developers,” Labrie said. “Integrating food production in buildings is not as easy as it looks. You have to sacrifice very expensive commercial or condo space. And so our solution enables them to monetize their underground space.”

(Techcrunch)

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.

(VAN) Attempts to bring down the price of the Japanese staple have had little effect amid a cost-of-living crisis.

(VAN) Fourth most important food crop in peril as Latin America and Caribbean suffer from slow-onset climate disaster.

(VAN) Shifting market dynamics and the noise around new legislation has propelled Trouw Nutrition’s research around early life nutrition in poultry. Today, it continues to be a key area of research.

(VAN) India is concerned about its food security and the livelihoods of its farmers if more US food imports are allowed.

(VAN) FAO's Director-General emphasises the need to work together to transform agrifood systems.

(VAN) Europe is facing its worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth since the start of the century.