May 29, 2025 | 12:46 GMT +7

May 29, 2025 | 12:46 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

May 29, 2025 | 12:46 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

The article “Preserve Water, Preserve Land, Preserve People of Ca Mau” reflects the severe drought and saltwater intrusion during the 2023 - 2024 dry season in Ca Mau. It highlights that Ca Mau has not yet benefited from Phase 1 of the Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system, and the residents of Ca Mau are anticipating investments in Phase 2. This system aims to provide a surface water supply to Ca Mau, reducing groundwater exploitation and mitigating the current issue of land subsidence.

Ca Mau province was not included in the investment targets for Phase 1, which explains why it has not yet benefited from the Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system. However, Section 11: “Issues to note in subsequent stages” in the Prime Minister’s Decision approving the Phase 1 investment policy includes the following statement: “Additional planning for certain components in the Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system will benefit Phase 2. Research the scientific basis and propose solutions to store and supply fresh water for agricultural production, aquaculture, and daily life under drought conditions, adapting to climate change, subsidence, and hydropower dams on the upper Mekong River, affecting the Ca Mau Peninsula region (including Can Tho city, Hau Giang, Soc Trang, Bac Lieu, Ca Mau provinces, and part of Kien Giang province).” Therefore, the expectation for a surface water supply solution for Ca Mau in Phase 2 of the Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system is well-founded.

Producing water to supply fresh water for daily life and economic sectors falls under the construction industry’s responsibility. Given the current conditions in Ca Mau, exploiting groundwater for domestic water supply in areas far from surface water sources is unavoidable. All living beings need fresh water, and human life is paramount. Thus, until a surface water source becomes available, groundwater exploitation for daily life in Ca Mau during the annual dry period is inevitable. Opposing this necessity is unrealistic and, to some extent, lacks empathy.

The supply of raw water to water supply plants is carried out by the Irrigation sector. According to the 2017 Irrigation Law, irrigation is defined as a combination of solutions for storing, regulating, transferring, distributing, and draining water for agricultural production, aquaculture, and salt production. It also includes contributing to water supply, drainage for daily life and other economic sectors, preventing and combating natural disasters, protecting the environment, adapting to climate change, and ensuring water security. This comprehensive role of irrigation explains why the Prime Minister emphasized the importance of Phase 2 of the Cai Lon - Cai Be Irrigation System. Only when water supply plants in Ca Mau are provided with raw water through irrigation can groundwater exploitation be minimized and eventually replaced by surface water sources.

A surface water supply solution is needed for Ca Mau to minimize groundwater exploitation and overcome land subsidence. Photo: Archive.

The need for freshening and supplying fresh water to the Ca Mau Peninsula, including Ca Mau itself, is not a new issue.

The French dug the Quan Lo - Phung Hiep canal between 1905 and 1918, enabling boats to travel from the Ganh Hao River to Ho Chi Minh City and vice versa. They also dug several other canals to supply fresh water and facilitate transportation within the Ca Mau Peninsula. In 1940, a project to prevent salinity in the My Thanh River at the Co Co location (near the mouth of the My Thanh River) was researched and designed. Although construction began in 1944, it was halted due to the Japanese coup. In 1970, the Saigon government contracted with the Japanese firm Nippon to survey and design the My Thanh salinity prevention project, completing the design report in 1974. This project included a complex of salinity prevention works on the My Thanh River at the Co Co location.

After 1975, the Vietnam Irrigation sector absorbed the results of previous research and preliminarily studied the planning of the entire Ca Mau Peninsula. They planned to supply fresh water from the Hau River to the entire region east of the Ganh Hao River. Additionally, they selected a plan to build a complex of works to prevent salinity and retain freshwater on the My Thanh River at Co Co (construction started in 1996, but due to limited capital investment capacity, it had to be postponed indefinitely).

The program to provide fresh water to the Ca Mau Peninsula, including Ca Mau town (now Ca Mau city), was supported by the World Bank and divided into three projects: Quan Lo - Phung Hiep, Tiep Nhat, and Ba Rinh - Ta Liem. Each project was financed with preferential loans and included several salinity prevention sluices and one freshwater canal, named after the central canal axis of the project.

During implementation, there was an incident in 2001 when the Lang Cham dam broke. This coincided with the flourishing shrimp farming movement in Ca Mau and the peak of the rice and shrimp dispute in Bac Lieu. Following the incident, the last section of the Quan Lo - Phung Hiep canal, originally intended to be a freshwater canal, became a saltwater supply canal for the rice and shrimp production area (brackish water shrimp farming) in Hong Dan and Phuoc Long districts of Bac Lieu province. This disruption not only interrupted the goal of providing water to Ca Mau but also placed it in a difficult situation. The aspiration to supply fresh water to Ca Mau was missed, becoming a “debt to remember” for irrigation planners in the Mekong Delta, as confessed by Dr. Nguyen Xuan Hien, former Director of the Southern Institute of Regional Irrigation Planning.

The ambition for sweetening is a long-held desire of the people, with a history stretching from ancient times to the present, through colonial and imperialist periods, and continuing into the era of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. This aspiration remains unchanged throughout the country, in the Mekong Delta, in the Ca Mau Peninsula, and particularly in Ca Mau. The disappointment, pain, and debt felt by the irrigation community have persisted. Now, during the peak of the harsh drought in the 2023-2024 dry season, the extreme endurance has transformed into a cry of expectation!

Since the incident of the Lang Cham dam destruction, the Irrigation industry has quietly learned from these bitter lessons and innovated its methods to meet the realities of life, aligning with the people's needs. They have continuously sought new ways to bring fresh water to Ca Mau. Here are the specific steps taken:

Based on the dispute between rice and shrimp farming in Bac Lieu and between Bac Lieu and Soc Trang, the “Soc Trang - Bac Lieu Fresh and Salt Water Demarcation System” project was initiated. This project was a situational countermeasure when salinity penetrated Nga Nam Town.

- During the process of proposing the investment policy for Phase 1 of the Cai Lon - Cai Be Irrigation System, more profound research was conducted across the entire Ca Mau Peninsula. This comprehensive study included all aspects of natural disaster prevention and control, environmental protection, climate change adaptation, and water security. The approach was both systematic and open, oriented towards thorough planning.

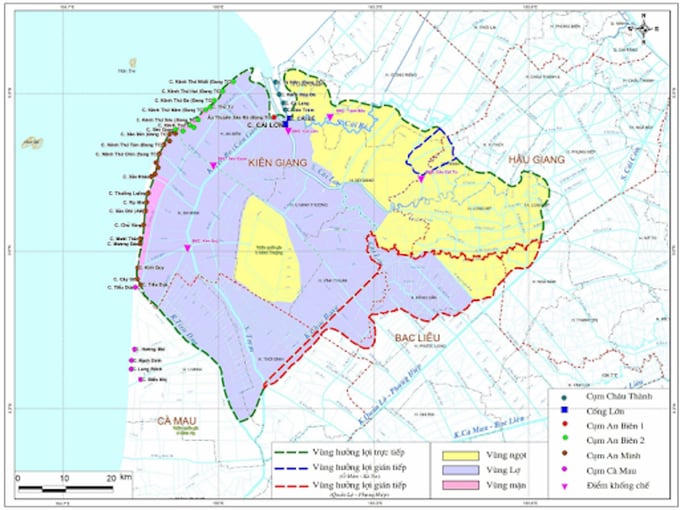

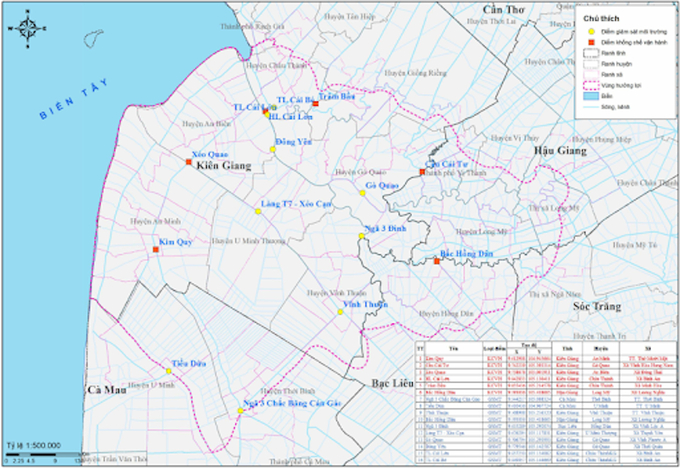

+ The yellow area on the map in Appendix III below represents the freshwater area after completing the Phase 1 construction investment project of the Cai Lon - Cai Be Irrigation System. This phase includes four components: the Cai Lon sluice, the Cai Be sluice, the dike connecting the Cai Lon and Cai Be sluices with National Highway 61, and the Xeo Ro sluice added later thanks to saved capital. This is in conjunction with the Ninh Quoi lock sluice and the Soc Trang - Bac Lieu fresh and salt water demarcation system. This illustrates that the shortest supply route for Ca Mau city must start from the highest point of the red dashed line (Nga 3 Dinh because it coincides with the yellow environmental monitoring point at Nga 3 communal houses on the map in Appendix IV). From Nga 3 Dinh, the water flow can continue along the Cai Lon river branch canal, called Xeo Chit canal, and follow the Chac Bang canal (continuous red dashed line) straight to meet Trem river (the blue dashed line junction with the red dashed line), covering about 40 km.

The current status map of Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system (Attached with temporary operating procedures for Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system).

On this map, in the middle of the brackish water area (purple), there is a freshwater area (yellow) encompassing U Minh Thuong National Park, where melaleuca trees grow. This demonstrates that even nature has its sweet and magical transformation, inspiring people to follow its example!

Map of environmental control and monitoring points of Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system (Attached with temporary operating procedures of Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system).

- After the “Tac Thu Construction Cluster and West Coast Irrigation Works” project is completed (the Feasibility Study Report was approved in July 2022, and it is currently in the stage of handover, receiving assets of the Tac Thu lock culvert item from the Ministry of Transport to prepare for the construction phase), the purple area will control salinity from the Doc river and Ganh Hao river. However, this project will not significantly impact the flow of fresh water on the Xeo Chit canal and Chac Bang canal.

- The further spread of fresh water from Dinh Junction along Chac Bang canal towards Trem river and Ca Mau city depends on how the water supply from the Hau river into the project area will be managed during Phase 2 of the Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system. The remaining water will be transported by the construction industry via pipeline to the water plant. In the document “Summary Report of Additional Consulting for the Bidding Package Survey and Preparation of Construction Investment Project,” the Cai Lon - Cai Be sluice project in Kien Giang province (established in 2018), the Southern Institute of Hydrological Sciences mentioned dredging Thot Not canal, KH6 canal, and the project cluster on the east bank of Chac Bang canal and Trem river to serve this goal.

The farmer's 4ha rice field has already prepared the land, waiting for fresh water to cultivate. Photo: Archive.

The above presentations demonstrate that sweetening is an irreversible natural process, an eternal human desire, and must be adapted to the emerging needs of life. There is a saying: “When debtors remember to pay, debtors forget to collect.” However, it seems that “The trees want to be quiet, but the wind won’t stop.” There remains unnecessary noise about this issue, attributing all the consequences of hot weather and subsidence to sweetening and the Irrigation industry. Here are a few examples:

“Associate Professor Dr. Le Anh Tuan, Scientific Advisor of the Climate Change Research Institute (Can Tho University), stated that some projects were invested with the 'ambition' to prevent salinity and bring in fresh water, but were ineffective and even created negative effects due to a lack of water.

"In extreme times like 2016, 2020, and this year, in some places such as Ca Mau, there was heavy subsidence; in some places in Tran Van Thoi, it was up to 2 meters and happened very quickly, even though the locality tried to restrict vehicles and reduce loads. However, even at night when there were no vehicles running, sudden subsidence still occurred," he said.

According to him, the lack of fresh water while salt water is prevented from entering causes the water pressure on the shore to no longer exist, resulting in sudden land collapse. “We want to have fresh water, but sometimes this leads to other consequences, and the damage is not small,” Mr. Tuan said.

According to the scientific advisor of the Climate Change Research Institute, it is necessary to assess the aforementioned damages to determine whether it is essential to continue efforts to sweeten the land for rice production.”

(Information from April 2, 2024: Sweetening project in the Mekong Delta and 'downside' in reality - Source).

The fundamental scientific issue here is that the dyke and sluice systems in this area are not designed as permanent freshwater structures; they only maintain fresh conditions during the dry season. Preventing saltwater intrusion is an operational error, not a construction flaw. The reasons why fresh water has not reached this area have been discussed above. The fact that people bring plastic cans to public taps to get water in the Go Cong area is due to a 20%-30% decrease in dry season rainfall this year. This shortage indicates that sweetening measures need to be increased, not reduced.

Dr. Duong Van Ni, Chairman of the Mekong Conservancy Foundation (MCF) and an expert on biodiversity in the Mekong Delta, noted that even during the French colonial period, the digging of the Quan Lo - Phung Hiep canal was intended to bring fresh water to the Ca Mau Peninsula. “But from that time until now, it is a proven fact that freshwater from the Hau River cannot reach there.” (Information from April 19, 2024: Understanding to adapt to drought and salinity (part 2): ‘Pour in’ billions to sweeten or to adapt?).

The reasons why Hau River’s freshwater has not yet reached Ca Mau and the methods to bring fresh water there have been clearly explained above. Dr. Duong Van Ni further explained that the Hau River lacks branches reaching the West Sea or bringing fresh water to Ca Mau, partly due to the mechanism of saline soil formation:

“Alluvial particles must replace their chemical composition if they want to settle. Specifically, in a freshwater environment, they carry ‘ions’ such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which are non-saline and very light. However, when the sediment particles enter a saltwater environment, larger ‘ions’ such as sodium, chloride, and sulfate replace the fresh ions.”

At this time, the sediment particles become heavier and can overcome the push of salt water to settle, forming soil. However, this soil is salty because it travels to the sea and then circles back in to settle. This also explains why the Hau River from Chau Doc (An Giang) down to Soc Trang has no branches going to the West Sea nor any branches bringing fresh water down to Ca Mau” (!).

Dr. Duong Van Ni also explained that in the Ca Mau Peninsula region, if left to dry, there will be two consequences: (1) an increase in surface layer salinity and (2) an increase in surface layer alum. Therefore, the best way to control this is to keep the soil wet throughout the year, which means adding salt water from the sea to "smother" alum and reducing salinity. This is the most basic mechanism of this land and raises the question: “The purpose of investing in freshwater projects in the Ca Mau Peninsula is to create a source of fresh water for production and daily life. However, will the story of money being poured in but the results not being as expected continue to happen, especially given the characteristics of this land being ‘alum and salty’ soil?” (Information from April 18, 2024: Understanding to adapt to drought and salinity (part 1): Salty soil, fresh soil, and how the ancients handled it - Source).

In fact, each river delta is formed by the dynamics of the river, ocean waves, and coastal currents interacting with the coastal terrain. The fact that the Mekong River's alluvial particles reach Ca Mau is also a consequence of the interaction of these four factors. Therefore, the opinion that the formation of the Hau River tributaries is partly due to the mechanism of salty soil formation when alluvial particles reach the sea is unfounded and shows confusion about cause and effect (the purpose of such an explanation remains very difficult to understand). As for keeping the soil (fields) wet, either salt water or fresh water is fine. If there is no fresh water, salt water must be used (though more fresh water is always better).

Therefore, it is impossible to deny the benefits and necessity of investing in sweetening projects due to their expense.

Centralized rural water supply projects need to be invested.

President Ho Chi Minh once said, “If there is land and water, the people will be rich, and the country will be strong. Water can be beneficial but also harmful; too much water can cause water logging or floods, while too little water can lead to drought. Our mission is to harmonize land and water to improve people's lives and build socialism.” Drought means the absence of fresh water, leaving only salt water (also known as saline drought). Brackish water, a mixture of fresh and salt water in a certain ratio, provides a growth environment for many valuable species. Objecting to sweetening is unnecessary because it is essential for harmonizing land and water, as well as balancing salt water and fresh water to better serve the needs of humans and all species.

The Cai Lon - Cai Be irrigation system succeeds the Ca Mau Peninsula Freshening Program with the goal of controlling salinity, resolving conflicts between coastal aquaculture and agricultural production areas in Kien Giang, Hau Giang, and Bac Lieu provinces within the Cai Lon - Cai Be river basin. Simultaneously, it aims to contribute to stable fisheries development in Kien Giang’s coastal areas, proactively respond to climate change and rising sea levels, create fresh water sources for coastal areas to alleviate dry season water shortages, and prevent forest fires, especially during drought years. This system will contribute to stable socio-economic development, making Ca Mau's land and water better regulated and its people healthier, happier, and more prosperous.

Translated by Quynh Chi

(VAN) The mutual export of agrifood products between the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) must occur again without certification, border controls or other red tape. This was agreed at the UK-EU summit.

/2025/05/22/5121-2-173645_677.jpg)

(VAN) NBSAP Tracker identifies strengths and areas for improvement in the National Biodiversity Strategy, based on each region’s priorities and capacities.

(VAN) The draft amendment to the Circular on rice export trading stipulates a periodic reporting regime for rice exporting enterprises.

(VAN) Dong Thap farmers attained an average profit margin of 64% during the summer-autumn 2024 crop (first season), while An Giang and Kien Giang farmers followed with 56% and 54%, respectively.

(VAN) As a doctoral student doing research on renewable energy and electrification at Harvard University, the author shares his musings on electricity, nature, and countryside memories.

(VAN) The decree on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) ensures transparent management and disbursement of support funds, avoiding the creation of a “give-and-take” mechanism.

(VAN) Hue City rigorously enforces regulations regarding marine fishing and resource exploitation, with a particular emphasis on the monitoring of fishing vessels to prevent illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.