June 21, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

June 21, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

June 21, 2025 | 02:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

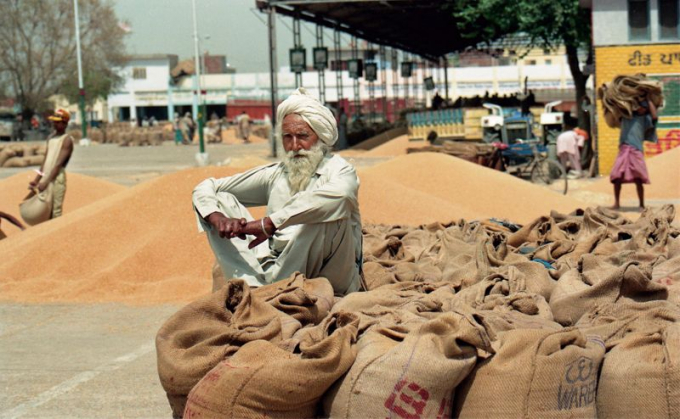

The number of people who are engaged in farming has increased steadily since early 2019. Photo: Tribune

Farmers are in trouble once again, even though they have produced more crops and their produce is fetching better prices. But to understand this, we will have to take a detour into basic national income accounting. Every three months, India’s ‘sarkari’ statisticians release data on the state of our economy. One key metric is Gross Value Added. It tells us how much additional value has been generated in those three months in the major sectors of our economy. This is calculated by adding up the market value of all goods and services produced in the economy and subtracting the value of all inputs and raw materials, so that there is no double counting.

The trouble is that this does not immediately tell us whether our economy is growing in terms of the actual goods and services produced. That is because it is possible for the total output in the country to fall, but its money value to rise because of high inflation. To get a ‘real’ comparison of economic growth, the market value of output has to be ‘deflated’ by the average price prevailing in each sector.

A quick example will explain this. Suppose your company produced 10,000 batteries and sold them at Rs 10 each in 2019. The market value of your output was Rs 1 lakh. In 2020, you could only produce 8,000 batteries, but you managed to sell them for Rs 15 each. The market value of your output is now Rs 1.20 lakh. In money terms, you have earned 20 per cent more than the previous year, but your actual output has dropped by 20 per cent. If the market value of your output is deflated by the 50 per cent rise in the price of batteries, we will realise that the actual output fell, instead of rising.

We need both the numbers to understand the economy’s current state. The ‘nominal’ or the value of output in current prices gives us a sense of the money going into the hands of people, while the ‘real’ or the inflation-adjusted value of output tells us what they can buy with their current income. These two numbers also give us a sense of how income is getting distributed across sectors. And, the latest data shows us that India’s farmers are in deep distress, even though on the face of it, things look better.

In the first quarter (Q1) of this fiscal year (FY), which is the three-month period between April and June 2021, the farm sector added about Rs 8.8 lakh crore of value in current market prices. In other words, we can say that as a whole, all those who are involved in the various parts of the agricultural chain, made an equivalent amount as income in Q1.

Since farming is a seasonal occupation, the right way to gauge growth is to compare it with Q1 of last year. That gives us a growth of roughly 11 per cent. So, if farmers earned Rs 200 last year, their income has risen to Rs 222 this year. Let us assume that they consumed all of the Rs 200 they earned in Q1 of 2020. Let us also assume that this year their consumption remained exactly at the same level. We can estimate how much they had to spend by looking at the inflation that rural India faced in this period. Rural retail inflation was about 5.5 per cent in Q1, so we can say that the farming community spent Rs 211 this year to simply stay at the same level of consumption.

But note what has happened here. Last year, farmers spent everything they earned. This year, they actually saved money. They earned Rs 222 but spent only Rs 211, ending up saving Rs 11. In fact, we can argue that farmers, as a whole, had the opportunity to consume more goods and services and save at the same time. In other words, the data suggests there was a significant improvement in ‘real’ income of farmers.

However, this ignores one fundamental change that has taken place in rural India over the past two years — reverse migration. The number of people who are engaged in farming has increased steadily since early 2019. So, to gauge how the average farmer has been affected by the rising output and higher prices, we also need to compare how many more people are working in the farm sector.

The Centre for Monitoring India’s Economy employment data shows that the number of people working in agriculture has risen from 138.6 million in Q1 of 2020 to 149.1 million in Q1 this year. If we take the market value of agricultural output and divide it by these numbers, we can get a proxy for average ‘nominal’ income per agricultural worker in these periods. That has risen from Rs 57,071 to Rs 58,939, or just 3.3 per cent.

So, if an average farmer earned Rs 200 last year, their income this year has increased to a little less than Rs 207. Just as in the previous example, we assume that the farmer spent everything they earned last year. This year to retain the same level of consumption, the farmer would have had to spend Rs 211, because the average retail inflation in rural India was 5.5 per cent. In other words, farmers would have had to borrow Rs 4 to stay at their same level of consumption. Their other option would have been to cut back on consumption.

In fact, it is most likely that farmers had to spend much more in Q1 this year because of increased medical costs during the second wave of Covid. Official infection and fatality figures might not show it, but ICMR’s latest sero-survey and the various estimates of ‘excess’ deaths clearly suggest that there was a hidden Covid crisis in rural India this summer. That means, farmers would have spent more at a time when their average real incomes fell. These are clear signs of farmer distress which our official numbers have kept hidden away.

(TribuneIndia)

(VAN) Poultry production in Poland, which has only started recovering from devastating bird flu outbreaks earlier this year, has been hit by a series of outbreaks of Newcastle disease, with the veterinary situation deteriorating rapidly.

(VAN) Extensive licensing requirements raise concerns about intellectual property theft.

(VAN) As of Friday, a salmonella outbreak linked to a California egg producer had sickened at least 79 people. Of the infected people, 21 hospitalizations were reported, U.S. health officials said.

(VAN) With the war ongoing, many Ukrainian farmers and rural farming families face limited access to their land due to mines and lack the financial resources to purchase needed agricultural inputs.

(VAN) Vikas Rambal has quietly built a $5 billion business empire in manufacturing, property and solar, and catapulted onto the Rich List.

(VAN) Available cropland now at less than five percent, according to latest geospatial assessment from FAO and UNOSAT.

(VAN) Alt Carbon has raised $12 million in a seed round as it plans to scale its carbon dioxide removal work in the South Asian nation.